The present report was conducted in partnership between Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) and Synergy organization, with support from Adopt a Revolution initiative. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Adopt a Revolution or its members.

1. Executive Summary

It has been six years since the implementation of the Four Towns Agreement reached between armed factions and Iran in April 2017 with Qatari mediation. The Agreement, which provided for the evacuation of al-Zabadani and Madaya near Damascus, and the Shiite-majority Foua and Kafarya in northwest Syria, involved powerful non-state players including Lebanese Hezbollah, Islamic Movement of the Free Men of the Levant/Harakat Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra (Al-Nusra) and Jabhat Fatah al-Sham.

Surviving crippling years-long sieges, populations of the four towns dreamed of a better life but alas, the new reality brought them new forms of suffering.

Human rights activist, Ahmed Kwefati, from al-Zabadani currently residing in Idlib, northwestern Syria, described the impact of the Agreement on those forcibly displaced by it,

“We got separated from our families, friends, and relatives. We lost our property, jobs, and everything we built. We were forced to live away from everything we hoped for and loved.”

Abu Nidal, former director of the health authority in al-Zabadani, currently lives in Afrin, northwest Aleppo testified to STJ,

“Being uprooted from our land was the hardest thing for all of us. Our life here is miserable. The security situation and living conditions in the liberated areas are very poor. Those who do not have links with the armed factions suffer a difficult financial situation; I am the biggest example. We also suffer emotional instability due to the fact that our fate and that of the region hinges on international polarizations. What is disappointing is that our brothers in the Syrian National Army have become mercenaries in every sense of the word.”

Roaa (a pseudonym), an activist from Madaya currently residing in Idlib, confirmed that initially, civilians who were bussed from al-Zabadani and Madaya did not realize that they were evacuated under an agreement; their only concern was to escape the appalling humanitarian situation they were suffering under siege, where they died of hunger and diseases due to severe lack of food and medicine. Nevertheless, later they were shocked by this new bitter reality. Roaa recounted,

“Effects of any crime cannot be noticeable at first; the same goes for the Four Towns Agreement. When we arrived at Idlib we were so happy, but after a while, we were shocked by the reality here. Some people ended up wishing they stayed in the siege. This was mainly due to continued violations by the armed groups in control of the region.”

The situation of those who remained in al-Zabadani and Madaya is no better, due to poor security, drug trade – under the cover of Lebanese Hezbollah and the 4th Armoured Division –, and property seizures. Local sources confirmed that the Syrian Government (GOS) arbitrarily seizes the property of civilians, especially those arrested or prosecuted, under alleged charges of terrorism.

As for the displaced from Foua and Kafarya, their suffering is not less heavy despite the different circumstances and destinations of their displacement. Those displaced from the Shiite-majority Foua and Kafarya that were encircled by rebels’ Army of Conquest/Jaish al-Fatah, spread into different regime-held areas including, Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Latakia, and Tartus. Notably, the two towns were fully evacuated from their original people.

Kafarya & Foua Facebook page published a post describing the pain of displacement saying,

“We also have land that we miss every speck of its dirt. We miss the homes that we built stone by stone, the fig and olive trees that we watered with the sweat of our brows and the blood of our martyrs, the shops and the noise of their keepers, and our loved ones embraced by its soil. We also have a land, a case, we have a forgotten land that we long to return to and be buried in. We became lost after we left our land; no homes shield us, no warmth fills our relations, and no soil embraces our bodies.”

Leaving their homeland, the people of Foua and Kafarya lost their properties to the armed faction in control of Idlib. That was cited in a study published by The Day After (TDA) organization in December 2020 that said,

“The HTS and the other rebel factions in the region like the Islamic Movement of the Free Men of the Levant/Harakat Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya and the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) took over private properties systematically in the evacuated areas including Foua, Kafarya, and al-Ghassaniyah village in rural Jisr al-Shughur. While most of these properties were not changed physically nor their ownership transferred, as confirmed by employees in the cadaster, they are held forcibly by the armed factions who invest in them by leasing or settling families of their fighters.”

Civilians were willing to cave to any solution that would free them of siege, even if the price was their homes and property. Although the GOS and relief organizations, including the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), provided displaced families from Kafarya and Foua with financial assistance to cover rent and other expenses, it has not informed the families for how long the assistance will continue, which created a sense of insecurity among them.

A displaced from Foua currently residing in Slanfah in rural Latakia stated to the Syria Direct website,

“We do not feel like we can live a normal life here. We do not have homes here; it is not our city. We need what anyone needs to live. We want to provide for our families. We want houses; we want to work. We want to return home.”

For its part, Amnesty International documented in a report entitled “We Leave or We Die; Forced Displacement under Syria’s ‘Reconciliation’ Agreements”, the violations associated with displacement agreements reached between the GOS and armed opposition groups under the auspices of international sponsors between August 2016 and March 2017, and led to the displacement of thousands of residents from Daraya, eastern Aleppo city, al-Waer, Madaya, al-Zabadani, Kafarya, and Foua.

The report says,

“Thousands of civilians forcibly displaced by these agreements are now suffering dire conditions; some are living in makeshift camps with minimum access to humanitarian aid and essential services, while others are struggling to cover their rent and other expenses such as water and electricity. The vast majority of them are unable to return to their homes. Meanwhile, the Syrian government is pressing ahead with measures that include requiring security checks for land and property transactions, seizing the homes of some of those displaced, and replacing old records, making it hard to prove ownership rights or to demand remedies.”

Among the consequences of the agreement is the demographic change in the covered areas, which is the biggest sect-based demographic change in Syrian history.

Qatar, which was a sponsor of the agreement, cared a little about the potential effects of the Agreement as it focused on its part of the deal, especially the issue of the Qatari royals who were kidnapped while hunting falconry, by Shiite militia led by Iranian general Qasem Soleimani in December 2015. Robert F. Worth, published a piece in the New York Times on March 14 under the title “Kidnapped Royalty Become Pawns in Iran’s Deadly Plot”, citing testimony by one of the freed Qatari royals detailing on the swap deal that cost Qatar about a billion dollars.

2. Methodology

This joint report between STJ and Synergy aims to highlight the events preceding and after the implementation of the Four Towns Agreement and the role of international actors in them. The report will explain the situation of those displaced by the Agreement, the difficulties and violations they are facing, especially those related to housing, land, and property rights, the impediments to their return, and will make recommendations that may mitigate the effects of the Agreement on them.

The present report is one in a series of reports discussing the effects of international agreements that led to mass displacements and thus to demographic changes in Syria.

The report is based on the outcomes of a dialogue session held on 17 June 2023, attended by locals and activists from al-Zabadani, Madaya, and Rif Dimashq. Notably, representatives from Foua and Kafarya could not attend for safety fears due to their presence in regime-held areas.

The session discussed the background, implementation, and effects of the Agreement. The attendees suggested solutions to prevent the further radicalization of the demographic change and made related recommendations. For the purpose of this report, we conducted online interviews with locals of al-Zabadani and Madaya residing inside Syria and abroad. The interviewees elaborated on the Agreement, told stories about the suffering they faced and their experiences in coping with the new reality, and shared their future aspirations.

We also sent questions to journalists and activists from Foua and Kafarya via the Internet, but did not receive any response.

Notably, to recover the gap resulting from the inability to reach out to witnesses from Foua and Kafarya, we detected online interviews and reports showing the suffering people of the two towns underwent during the siege, on the displacement way, and at their final destinations.

The present report is also based on legal research and reports as well as news articles from reliable open sources.

3. Introduction

On 12 April 2017, the green buses set off al-Zabadani and Madaya announcing the end of the devastating siege enforced by the GOS and Lebanese Hezbollah in July 2015. The Agreement was the straw that the people of the two towns clutched at to survive the tragic living conditions, the indiscriminate non-stop bombardment, and starvation which turned them into living skeletons. The people accepted the Agreement because they saw it as the lesser evil and hoped it to put them on the route to resurrection and compensation.

The fate of al-Zabadani and Madaya was linked to that of the 400 km away towns of Foua and Kafarya, which were unlawfully besieged by armed opposition groups, who arbitrarily restricted access to humanitarian and medical aid and confiscated medical supplies from aid convoys. They also shelled civilian areas using explosive weapons with wide area effects. The siege on Foua and Kafarya started in March 2015 and ended in July 2018 with the full evacuation of the two towns’ population after their conditions worsened dramatically.

While the Agreement was presented as a humanitarian solution to the four towns’ crisis, residents of the four towns became a bargaining chip, their fate used as leverage in achieving strategic interests during negotiations between the parties to the conflict. Under the Agreement,

- Al-Assad retook two threatening rebel towns near Damascus;

- Iran stretched across Syria into areas of Hezbollah in Lebanon and saved the lives of the Shiites of Syria’s north;

- Armed opposition groups extended full control over Foua and Kafarya, took their original people’s homes with all their contents as “war spoils”, settling rebel fighters coming from Rif Dimashq, Homs, and Daraa in some and investing in others through leasing;

- Qatar managed to release the 28 kidnapped royals of its ruling al-Thani family after 16 months of detention by the Iraqi Hezbollah Brigades, backed by Iran, in exchange for a ransom of a billion dollars.

Notably, to recover the gap resulting from the inability to reach out to witnesses from Foua and Kafarya, we detected online interviews and reports showing the suffering people of the two towns underwent during the siege, on the displacement way, and at their final destinations.

| The Four Towns Agreement stipulated,

The evacuation of 3,800 people, including fighters, from al-Zabadani towards Idlib, and those who wished to leave al-Zabadani, Madaya, and Bloudan to the north. The evacuation of 8,000 people, including pro-government militias, from Foua and Kafarya towards Aleppo. The exchange of prisoners and bodies between the two parties, the release of 1,500 detainees from regime prisons, mostly women, allowing access to humanitarian aid, and arranging truces in south Damascus starting from the Yarmouk Camp. The resolve of the issue of 50 families from al-Zabadani and Madaya stuck in Lebanon, in exchange for removing the entire population of Foua and Kafarya in two batches. Notably, in 2018 the geographical scope of the Agreement was extended to include Al-Hajar al-Aswad and the Yarmouk Camp south of Damascus. |

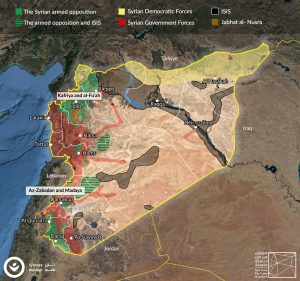

A map showing areas of military control in Syria in late 2015.

4. Recommendations

The dialogue session that was held by STJ and Synergy with the attendance of locals and activists from al-Zabadani and Madaya, produced the recommendations below,

- Pressure State actors implicated in the Syrian file, especially those party to displacement agreements, to nullify these agreements, apologize to the Syrian people for their drastic consequences, redress their victims, and make their texts public.

- Urge Syrian civil society organizations, human rights ones in particular, to assume their responsibilities in the documentation of violations that occurred on all Syrian territory since March 2011 including, of course, those related to property, impartially and professionally. The organizations must carry out awareness-raising and advocacy campaigns to highlight the importance of property violations documentation and its role in protecting the rights of IDPs and refugees, which contributes to their voluntary and safe return to their areas of origin. Thus, organizations must prompt IDPs and refugees to keep their ownership documents and reject displacement agreements and their results, especially the demographic change.

- Consider gender sensitivity and prioritize addressing women’s property rights, especially those affected by the Agreement, along with adopting Pinheiro Principles as a reference on women and girls’ property and housing rights.

- Appeal the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (CoI Syria) through Syrian civil society organizations to pay more attention to documenting property rights violations in all of Syria and to address the processes of demographic change resulting from displacement agreements.

- Pressure the GOS to fulfill its legal duties towards the citizens, including revealing the fate of detainees and missing persons, facilitating the issuance of death notifications, birth certificates, marriage certificates, and other official documents, which are essential to prove property ownership, especially for Syrians in areas outside its control.

- Provide in the Constitution for the primacy of international treaties and agreements that the GOS ratified and will ratify, especially those related to human rights and fundamental freedoms, including, of course, the right to property and consider Pinheiro Principles as an integral part of Syria’s national laws.

- Pressure the GOS to; consider property seizures and ownership transfers conducted after March 2011 invalid, repeal urban planning laws and eliminate their consequences, adopt the pre-2011 real estate records, and consider information in the post-2011 records as disputable proof.

- Pressure the Syrian government (GOS) to declare the displacement agreements invalid, since it was not a party of, as the Syrian Parliament did not ratify them, and because they contradict Article 34 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which states, “A treaty does not create either obligations or rights for a third State without its consent.”

5. Legal Opinion

Article 75 of the current Syrian Constitution stipulates that the People’s Assembly has the exclusive authority to approve international treaties and conventions so that they become effective and binding to the Syrian government and people. However, the People’s Assembly did not ratify the Agreement subject of this report since the Syrian government was not a party to it in the first place; the Agreement was concluded between Iran and affiliated Iraqi militias, Syrian armed opposition groups, and Qatar. As such, the Agreement is not binding on Syria or its people and thus cannot be invoked against them.

The Four Towns Agreement led to a myriad of violations against locals in the areas it covered. The violations included killing, arbitrary arrest, forced disappearance, torture, forced displacement, looting, and property seizure. Many of these violations may amount to war crimes and in some cases crimes against humanity. Parties to this Agreement take the full blame for these violations, thus they are legally responsible for impact removal, restoration, and compensation. In case restitution in kind is impossible, parties to the Agreemnet are obliged to compensate eligible victims who suffered material, moral, or physical damage from their actions.

The Syrian State, based on its responsibility to protect the fundamental rights of its citizens enshrined in the Constitution, including the right to property and the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the State,[1] must carry out its duties to protect its territory, citizens, and their rights and to demand the Agreement’s parties to assume liability for their acts.

Deportation and forcible transfer are defined as the forced displacement of one or more persons by expulsion or other forms of coercion. The term “forced” may include physical force, as well as the threat of force or coercion, such as that caused by fear of violence, duress, detention, psychological oppression, or abuse of power, or the act of taking advantage of a coercive environment.[2]

Any deportation of the civilian population that does not meet legal requirements is considered forced displacement even if conducted under agreements concluded between parties to the conflict autonomously or with third-party mediation. International law stipulates that displacing people forcibly from their areas of origin or areas in which they are lawfully present, is considered forced displacement unless the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons demand. Nonetheless, displacing civilians must be a temporary measure that ends as soon as the reasons for displacement cease to exist and must be implemented in accordance with the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement.

Reflecting on the Four Towns Agreement, the resulted displacements did not aim to protect civilians nor they were demanded by imperative military reasons. Moreover, the practices that followed this Agreement, which established a new de facto reality clearly indicate the purpose behind this Agreement which was changing demographics in the covered towns in proportion to the political ends of parties to the conflict.

Rule 129 of customary international humanitarian law (Customary IHL) states,

- “A. Parties to an international armed conflict may not deport or forcibly transfer the civilian population of an occupied territory, in whole or in part, unless the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons so demand.

- Parties to a non-international armed conflict may not order the displacement of the civilian population, in whole or in part, for reasons related to the conflict, unless the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons so demand.”

The legal framework on internal displacement pays particular attention to issues of property protection. All relevant parties must protect people from any practices that may, in any way, affect their enjoyment of their right to property including, plunder, confiscation, destruction, and legal or illegal transfer of ownership.

6. Difficulties for al-Zabadani and Madaya IDPs

The impacts of the Four Towns Agreement left on IDPs are several and lasting. The latter found themselves in a totally new environment in which they had to start from scratch and fight plenty of challenges, including financial difficulties, lack of employment opportunities, security threats, and societal differences.

Nisreen (a pseudonym) an activist from al-Zabadani currently residing in Afrin elaborated on her family’s suffering following their displacement,

“The first years of displacement were as difficult as uprooting. We did not have shelter or any other life basics. It was almost impossible for us to lease a house and equip it, as we did not have money or jobs. We felt adrift, especially since we were not adapted to the new environment, place, and rulers.”

Ola Burhan, a civic activist from al-Zabadani, currently residing in Afrin, confirmed that poverty was the worst suffering the IDPs faced. Ola narrated,

“The conditions of the injured deteriorated severely, especially those with limb amputations, as they needed periodic scraping and cleaning in the Turkish hospitals whose access needed prior permission. This is in addition to the difficulty of integrating into the new society, and that some families could not enroll their children in schools due to their failure to provide documents proving their grades.”

Ola added that in the first year of displacement, al-Zabadani IDPs congregating in Idlib and Ma’arrat Misrin established an autonomous civil registry to record their births, marriages, and divorces. However, later this registry went under the central administration in Idlib.

Mohammad Youssef, a veterinarian displaced from Madaya to Idlib, confirmed that the organizations that received the IDPs provided them with aid for only one month after which they had to search for tents or houses to rent amid severe financial difficulties. Mohammad explained,

“We left our homes with nothing but clothes and very necessary stuff. There was no free space in the buses to transfer our furniture or other homeware so we left them there. In the first year of displacement, we leased houses furnished with only a mattress or a mat. After the second or the third year, IDPs started buying some home supplies. We suffered in search for houses to lease; some IDPs preferred to stay in the houses set by the organizations on top of the mountains or in border towns far from frontlines such as Harem, Sarmada, and Ad Dana.”Under conditions of widespread unemployment, IDPs have managed to open their own business,

“I got back to my job as a veterinarian after I worked as a surgeon during the siege. Teachers, engineers, traders, blacksmiths, and butchers also went back to their businesses”, Mohammad added.

Mohammad said that most of the IDPs in Idlib struggle to afford their daily bread while the rich class, which is composed of money holders who work in money exchange or transfer or have shops in the shopping mall, is estimated to constitute less than 15% of the city’s population.

Mohammad touched on the problems in the educational system saying that families felt obliged to send their children to private schools, which cost about $200-300 a year per student, after they lost trust in public schools whose education became poor, especially in the last couple of years, due to negligence of their management staff and their failure to pay teachers’ salaries.

Roaa, an activist, talked about other kinds of difficulties she faced in Idlib. Roaa recounted,

“We were displaced several times due to the continued bombing. Three days after our arrival, a young man and his wife, among the displaced, were martyred as a result of the bombing, and their children remained alone facing life. Moreover, hostilities between armed factions increased the difficulties and led to the arrest of my brother and husband and the closure of my IT engineering department in the free Aleppo University by the HTS.”

Roaa noted that many IDPs returned to al-Zabadani because of their inability to bear the conditions they faced in Idlib especially, the lack of job opportunities, high rents, continuous bombing, arrests, and the chaos.

Nour Burhan, an activist from al-Zabadani, currently residing in Germany, confirmed that the arrests, deprivations of liberty, and other violations hardline factions in control of Idlib are committing, are not only directed to al-Zabadani and Madaya IDPs but affect all civilians in Syrian northwestern areas. These violations prompt many people in these areas to return to their hometowns despite the dangers and difficulties they may encounter.

For her part, Roaa confirmed that the GOS forces arrested many men and women upon their return under former malicious reports, or because their names were listed with those who chose to exit to Idlib. Some of the arrested women were held for days and others for months, while most of the men no one heard about them after their arrest and thus forcibly disappeared.

7. Madaya and al-Zabadani Today

Madaya and al-Zabadani after the siege are not the same as they were before it; they lost their tourism, agriculture, and trading features. Madaya and al-Zabadani once were major tourist destinations for Syrians as well as Gulf Arabs who owned 20% of their real estate. However, today the two towns are 80% devastated, and most of their population who used to work in farming lost their livelihood due to damage caused to agricultural lands, tree uprooting, and plains burning. Furthermore, landmines were planted in hectares of land surrounding agricultural lands, which made it almost impossible to cultivate them or even reach them. Moreover, Lebanese Hezbollah turned the whole area into a warehouse of weapons coming from Iran and a hotbed for drug production.

Activist Abu Nidal al-Souri described what happened to al-Zabadani saying,

“After lifting the siege and transferring us to the north, those who were displaced from al-Zabadani to its surroundings started to return to their devastated town. Meanwhile, regime loyalists (Shabiha) were looting houses before the eyes of their owners. Returnees are not allowed to move without permission and their condition is dire amid the absence of work. Fruit trees, for which al-Zabadani was famous, were uprooted by the regime and Hezbollah fighters with the aim of selling them as firewood. Furthermore, the water pumps on which the farmers rely to water their lands were stolen and most of the wells were backfilled, which increased locals’ suffering.”

In this contexts, activist Nour Burhan said,

“The overall situation in the town can be described as bad like in other regime-held areas. However, what makes it even worse is the burning of agricultural lands and al-Zabadani plain and thus the loss of agricultural infrastructure on which locals depend for their livelihoods. Moreover, most of the buildings are still demolished, and in many neighborhoods reconstruction or restoration is prohibited.”

Amjad al-Maleh, a civil activist from Madaya currently residing in Afrin sees that the spread of drugs and poor security conditions are the biggest threats to the region. Amjad explained,

“Madaya and al-Zabadani are today hotbed for drug trade under the cover of the 4th Armoured Division and Hezbollah. In Madaya four drug production factories are operating with the full knowledge and complicity of the international community. What is more, there is a plan to build a smuggling route from Homs to Lebanon via Qalamoun.”

Amjad added,

“This is coupled with the poor security situation, widespread theft, and illegal appropriation of houses. Furthermore, those who went to stay in the mountains renewed violent acts against regime figures. They recently killed Emad al-Tinawi, head of the Ba’ath Party division in al-Zabadani, while passing the road between al-Zabadani and Bloudan.”

| Al-Zabadani is of geopolitical importance, as it is located at the Lebanese-Syrian border, opposite the last points of southern Lebanon, which is a stronghold of Hezbollah. Al-Zabadani links Damascus with Lebanese Hezbollah as the main Damascus-Beirut road passes through it. Al-Zabadani is 54 km away from Damascus and was considered its tourist center, and it has the Presidential Palace. |

8. No ownership for Opponents in Madaya and al-Zabadani

The GOS seized the properties of its opponents by the force of law. In 2012, the GOS issued Law No. 19 (Counter-Terrorism Law) and Law No. 22 (Establishment of a Counter-Terrorism Court), which allowed it to seize the movable and immovable properties of opponents over alleged charges of terrorism. Furthermore, the GOS imposed precautionary seizure on the properties of locals of areas that revolted against it and expropriated the properties of displaced people and evaders of compulsory service in the Syrian Army. In this context Human Rights Watch (HRW) stated,

“The Syrian government is using its sweeping Counterterrorism Law and its recently established special court against human rights defenders and other peaceful activists….on charges of aiding terrorists in trials that violate basic due process rights.”

Activist Amjad al-Maleh confirmed that his property in Madaya was confiscated by a decision issued by the Counter-Terrorism Court and added,

“My name was listed with those of other individuals whom I could not identify except one. They framed me with a charge of joining a terrorist cell over which my property was seized and I was sentenced to death in absentia.”Amjad noted that many IDPs from al-Zabadani and Madaya discovered the seizure of their properties by accident; they were not informed of the seizure decisions.

Activist Ayham (a pseudonym) who hails from al-Zabadani and currently residing in Lebanon confirmed that his property was seized and he failed to return it. Ayham explained,

“Precautionary seizure mark was placed on the cadastral certificates of my properties so I cannot dispose of them nor can I remove the mark since it is security.”

Activist Nour Burhan had an intervention in this context saying,

“Several of the property seizures in al-Zabadani and Madaya were conducted fraudulently or by force. Seizing women’s properties was easier due to their legal and customary weakness.”

Civil activist Ali Nasrallah explained that the region was not affected by the appropriation Law No. 10/2018. However, real estate transactions were impeded by consequences of decisions by Counter-Terrorism Courts or by the absence of one of the parties to the transaction due to the dispersal of the region’s population between Damascus and northern Syria. Ali confirmed that because seizures were decided under law-based jurisprudence and were not reprisals, properties it is difficult to retrieve or claim. It is relevant to recall that property seizures were accompanied by deliberate destruction of civil records. In 2017, informed sources quoted senior officials in neighboring Lebanon as saying that they have been monitoring what they believe has been a systematic torching of Land Registry offices in areas of Syria recaptured on behalf of the regime. A lack of records makes it difficult for residents to prove home ownership. Offices are confirmed to have been burned in al-Zabadani, Darayya, Homs, and al-Qusayr on the Lebanese border, which was seized by Hezbollah in early 2013.

9. Effects of the Agreement on Kafarya, Foua Population

In 2016 and 2017, locals of Kafarya and Foua were evacuated in two batches under the Four Towns Agreement and were distributed in collective shelters in Latakia and Homs. In 2018, the full evacuation agreement was concluded and the last locals of the two towns were transferred to a temporary shelter in Jibreen, eastern Aleppo. Many IDPs complained about the scarcity of aid and the favor of families of Shiite militias’ fighters when distributing it, which prompted many IDPs to leave shelters and lease houses or enroll their children in these militias to secure their living. Some of the IPDs went to Sayyidah Zaynab southern Damascus for work and residence.

Since 2018, a large number of real estate in the areas surrounding Sayyidah Zaynab have been sold by their original owners to people from Kafarya and Foua, people affiliated with the Shiite militias, as well as Iranian, Iraqi, and Afghan Shiites. Analysts consider this as the beginning of a long-term plan that seeks a demographic change in the area to turn it into a Shiite area similar to Dahieh, south of Beirut.

Real estate brokers take advantage of the GOS’s decision not to allow these areas’ original people to return, to buy their properties, whether destroyed or habitable, for peanuts. Brokers call original owners, mostly rebel fighters, and threaten them with seizing their property if they refuse the unfair offers.

Almost the same happened in Aleppo where Iranian militias have settled, since 2018, locals of Kafarya and Foua in the homes of the displaced in the eastern neighborhoods including, al-Saliheen, al-Fardos, al-Mashhad, and Sukkari, and provided them with mattresses, blankets, food, and electric generators subscriptions.

Since early 2019, the Iranian militias started restoring uninhabitable homes with direct support from the Iranian Reconstruction Authority. The militias gave some of these houses to families of its fighters and leased others.

|

The towns of Kafarya and Foua are located in northern rural Idlib and were among the few Shiite-majority Syrian towns. After 2011, the two towns were no longer calm; their people rallied to support al-Assad while their surrounding Sunni towns were calling vociferously for his removal. In 2015, hardline Islamic groups took over the entire Idlib except for Kafarya and Foua, which were turned into military zones because pro-government-Hezbollah forces holed up there. The rebel groups used the two towns as leverage to impose their terms during negotiations the GOS and Lebanese Hezbollah. |

10. Disputes over Real Estate Ownership in Kafarya and Foua

After their evacuation in July 2018 by the Four Towns Agreement, Kafarya and Foua came under Islamic armed groups.

In Kafarya, the HTS took half of the houses while the other half was divided between the TIP and Ansar al-Tawhid.

As for Foua, it was divided into sectors. Each sector is fully controlled – with all the houses and shops it contains – by one of the controlling armed groups which are; the HTS, Army of the Free/Jaysh al-Ahrar, the Sham Legion/Faylaq al-Sham, Islamic Movement of the Free Men of the Levant/Harakat Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya, and Damascus Sons Gathering.

Today, Kafarya and Foua are inhabited by IDPs from Damascus countryside – mostly from Madaya and al-Zabadani – Homs, Daraa, and Quneitra.

Since 2018, disputes continue unabated between IDPs and armed groups over who would take what of the houses left by Kafarya and Foua locals. Factions forced IDPs to sign lease contracts with them and pay rents for the houses, which they considered their war spoils.

Notably, after the displacement of Kafarya and Foua original people, the contents of the two towns’ houses were looted, including furniture, electrical appliances, and cladding materials. Later the HTS auctioned off the houses’ stuff as “war spoils”.

The civil activist Ali Nasrallah confirmed that the real estate sells in Kafraya and Foua are not legally concluded with original owners, but with the “housing offices” of the armed factions.

Ali added that the largest number of al-Zabadani and Madaya IDPs is in Foua, and it got smaller in Kafarya, Idlib, and Afrin respectively. Ali said,

“The dire financial situation of al-Zabadani and Madaya IDPs left them no choice but to stay in the houses of Foua and Kafarya for free and put up with the factions’ practices which based on their belief that they gained the area as a ‘war spoil’, and thus they have the right to do whatever they want in it. However, other IDPs headed to other areas prompted by the availability of jobs and services.”

Activist Baraa al-Shami (a pseudonym) from Rif-Dimashq affirmed that IDPs came to Kafarya and Foua because of their dire financial situation and that they face many difficulties, including those related to the lack of basic services and the fragile infrastructure. Baraa added,

“Armed factions urged IDPs who arrived in Idlib to go and reside in Kafarya and Foua, especially since the rents in Idlib are high and may reach 150$ for a house per month. The factions told the IDPs that the houses that they would reside in Kafarya and Foua, are compensation for the houses and properties they left in their hometowns. We tried to convince IDPs not to accept the factions’ offers even if their financial situation demands.”

| In a statement issued on 6 August 2018, the Salvation Government demanded the transfer of IDPs staying in Idlib schools to Kafraya and Foua before the start of the school year. |

11. Long Displacement Routes

The suffering on the displacement routs never leave minds of those displaced by the Four Towns Agreement.

The civil activist Amjad al-Maleh recounted on the IDPs’ journey from Madaya to Syria’s north and the violations they faced saying,

“We left Madaya on 12 April 2017. We were around 2,700 people. We passed through many Syrian cities until we reached the Ramouseh station in Aleppo. Then, a bombing occurred in the al-Rashideen neighborhood near the buses carrying civilian evacuees from Foua leaving 100 dead mostly children. Among those who died, were people waiting for their relatives coming from al-Zabadani and Madaya. That was followed by a heavy presence of Iranian security forces and Russian military police accompanied by members of the SARC who treated us in a very bad way and provided no help. Our biggest fear then was that we would be killed in response to that terrorist bombing, so we instantly launched a media campaign confirming that we had no hand in the bombing.”

Amjad added,

“We arrived in the city of Idlib on April 14. There were no equipped shelters, so they distributed us to hospitals. On that day, organizations distributed aid, including food, to the IDPs with no consideration for the fact that they were deprived of food for years, eating only legumes and a few other kinds. This resulted in the sickness of many IDPs.”

| Al-Rashideen bombing as described by a displaced in “Empty Seats” book that documented the diaries of Kafarya and Foua siege,

“At about 3.00 p.m., a car came carrying chips for the children. They started calling for the children to get the crisps. Indeed the children, who had been hungry for two days and two nights, ran towards the car wishing to try the taste of the crisps which they had forgotten since the start of the dreaded siege. Suddenly, we heard the sound of a very strong explosion, and very quickly a thick black smoke rolled over us and fear struck our hearts. Everyone was screaming. Men were yelling at women to gather. The gunmen were running with their weapons in their hands. The car bomb detonated near the front buses of the convoy. Of course, these buses were burned with everyone on them. The whole scene was horrific, and no pen can describe what happened. The whole scene was horrific, and no pen can describe what happened. Blood, body parts, and corpses covered the place, and people rushed to look for their children, screaming, howling, and hitting their faces.” |

12. Return Conditions

Al-Zabadani and Madaya IDPs see that current conditions are not conducive for return yet, especially in the lack of a safe and neutral environment whose creation must be preceded by confidence-building measures related to accounting perpetrators and redressing victims.

In this regard, Dr. Mohammad Youssef said,

“Every expatriate hopes to return to his/her country sooner than later. Many people wish to return today rather than tomorrow, but the security grip in regime-held areas prevents this. Every person in Idlib, from the children to the elderly, are wanted for the regime whom we never trust. In many cases, returnees to regime areas were arrested at the first checkpoint an returned corpses to their families. Therefore, no return to al-Zabadani and Madaya until the regime is gone and the security grip fell, sectarianism and factionalism disappeared, and life got back to being normal, free and dignified.”

Activist Nisreen agreed with Dr. Mohammad saying,

“There is no hope for the IDPs to return without the downfall of al-Assad regime.”

In the same vein activist Ayham believed that it is difficult for the IDPs to return in this increasingly desperate economic time.

13. Conclusion

International actors who author and monitored the implementation of the Four Towns Agreement achieved their purposes at the expense of the civilians who lost everything they owned and had to start from scratch amid difficult circumstances as well as political, economic and social challenges.

The Agreement did not mention the possibility of the locals’ return to their areas in the future nor did it explain the fate of their properties (life savings); houses, lands, and shops.

Civilians forcibly displaced by the Agreement are now suffering dire conditions; some are living in makeshift camps with minimum access to humanitarian aid and essential services, while others are struggling to cover their rent and other expenses such as water and electricity. The vast majority of them are unable to return to their homes.

The seizure of the IDPs’ properties by the GOS and allied Iranians on the one hand and the armed opposition groups on the other along with the destruction and loss of ownership documents made former residents unable to prove their property rights or claim compensation.

One of the major consequences of the Agreement is the demographic change it brought which was the largest in the country on a sectarian basis. Actors involved in the Agreement must work to restore the forcibly displaced civilians’ rights and create the conditions for their voluntary, safe, and dignified return.

[1] The aforementioned agreements led to depriving the people of the four cities of their property, especially real estate, and forced them to forcibly move to other Syrian cities and towns without having any authority in this regard. This contradicts what is stipulated in the Syrian Constitution, especially in Articles 15 and 38.

[2] ICTY, Prosecutor v. Radovan Karadžić, Case No. IT-95-5/18-T, Public Redacted Version of Judgement Issued on 24 March 2016 – Volume I of IV (TC), 24 March 2016, § 489.