- Executive Summary

On 9 October 2019, Turkey launched the sweeping “Peace Spring” offensive into northeastern Syria, backed by several factions of the Syrian National Army (SNA), an affiliate of the Syrian Opposition Collation(SOC). In the aftermath of the operation, the involved factions established control over a territorial strip covering Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tal Abyad, and the areas in between. Soon after, the SNA-affiliated factions carried out large-scale pillages against private and public properties in the areas they controlled, including in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê city. The factions looted the contents of over 220 stores, warehouses, and industrial facilities in the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone, robbing the original owners of the targeted facilities of possessions worth millions of dollars.

The SNA factions responsible returned only a small collection of the items they looted from the industrial zone to owners, smelting or selling most of the pillaged contents to local Syrian or Turkish merchants.

The three partner organizations who contributed to this report— PÊL- Civil Waves, Hevdestî (Synergy) Association, and Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ)— obtained numerous testimonies confirming that the Sultan Murad Division, led by commander Fahim Issa, was the chief perpetrator of the assault on the industrial zone, where its division members sometimes pillaged, looted, and confiscated all the contents of targeted facilities. Another set of collected testimonies proved that the Mu’tasim Division, led by commander Mu’tasim Abbas, perpetrated a smaller segment of the thefts in the industrial zone. Notably, even though the Turkish army maintains an extensive presence in the targeted area, they enforced no measures to prevent the looting and pillage operations.

In addition to the industrial zone, the partner organizations recorded similar looting operations in the Peace Spring Strip— including Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, Tal Abyad, and the areas between them— perpetrated by the military factions operating in the region. The perpetrators, among them the Northern Hawks Brigade and Tajammu Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Gathering of Free Men of the East, pillaged public properties to extract structural brass used in the construction of target facilities, damaging power and irrigation networks, as well as several buildings and agricultural lands.

The testimonies collected by the field researchers with the three partner organizations demonstrate that the Ras al-Ayn Local Council, affiliated with the SOC’s Syrian Interim Government (SIG), was also implicated in the looting operations. The testimonies verify that the council facilitated the pillages, as well as the sale transactions of the looted structural metals, in return for money.

Pertaining to the sale transactions, an informed local source told STJ that metal sales in the “Peace Spring” strip were carried out with the consent of the governor of the Turkish city of Şanlıurfa. The source added that the governor coordinated the sales and played the intermediary between Turkish merchants and the two divisions of the Sultan Murad and al-Hamza/al-Hamzat. Importantly, Turkish authorities usually prohibit such imports to control competition with locally manufactured products, especially because the stolen materials imported from Syria are sold for prices below the standard prices on the Turkish markets.

In addition to exports to Turkey, STJ obtained information indicating that some of the looted materials were sold to the Syrian government. These transactions are arranged by merchants from Damascus, who mediate the operations between the government’s 4th Division on the one side and the opposition’s Ahrar al-Sharqiya and the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya on the other. STJ discovered that the looted items left the region three months after Operation “Peace Spring” through the Tufaha Crossing, headed to the Hamsho factories in government-held areas.

This report’s findings corroborate those unearthed by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic in their report of 14 August 2020, numbered (A/HRC/45/31). In section B, paragraph 49, the commission states the SNA-affiliated factions were “engaged in widespread and organized looting and property appropriation in Ra’s al-Ayn.”

Furthermore, the factions’ activities documented in this report constitute a blatant violation of a number of war laws, as well as several terms of the “historic agreement” between the U.S. and Turkey which lead to a ceasefire and put an end to the Turkish offensive into northeastern Syria. The lootings reported herein are at odds with the agreement’s fourth term, in which “the two countries reiterate their pledge to uphold human life, human rights, and the protection of religious and ethnic communities.” The operations also breach the seventh term, in which “The Turkish side expressed its commitment to ensure the safety and well-being of residents of all population centers in the safe zone controlled by the Turkish Forces . . . and reiterated that maximum care will be exercised in order not to cause harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure.”

The testimonies the partner organizations obtained confirm, beyond a doubt, that Turkey did not abide by the terms they signed. Furthermore, this report demonstrates that while Turkish forces were mostly passive to the reported violations, they were also sometimes engaged in activities that might amount to war crimes.

In order to deter armed groups from continuing their looting practices with impunity, PÊL, Hevdestî Association, and STJ propose that the United States expand the scope of the sanctions they imposed in September 2021 on the opposition-affiliated Ahrar al-Sharqiya faction to include the Sultan Murad Division and the Mu’tasim Division, as well as their commanders, in addition to the Ras al-Ayn Local Council, for perpetrating large-scale looting and confiscation of civilian properties, particularly of Syrian Kurds, in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê city.

Other Syrian organizations, like the Syria Justice and Accountability Center, described the U.S. designation of the Turkey-backed Ahrar al-Sharqiya as a positive step on the path to safeguarding human rights in northeastern Syria. Additionally, the center demanded that the U.S. widen the range of the sanctions to cover other armed groups, including SNA factions, notably the Suleiman Shah Brigade (also known as al-Amshat), which are committing human rights violations in the region with impunity. Furthermore, the center called for coupling the sanctions with diplomatic pressure to combat attempts at normalizing the Turkish occupation of northwestern Syria.

- Legal Analyses and Implications

According to Article 42 of the Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land in the 1907 Hague Convention,[1] Turkey’s presence in Syrian territories and its overall control of parts of it directly or through its proxy militias is considered an occupation. As clearly stated in Common Article 2 to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949,[2] such a situation is governed by the international humanitarian law of international armed conflicts. Accordingly, the violations referred to in this report against civilians and their properties within the occupied territories constitute clear violations of international humanitarian law and, in most cases, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, which are also considered war crimes.

Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention obliges the occupying power to take responsibility for the security and safety of civilians in the territories it occupies.[3] Moreover, Article 147 of the same Convention states that acts such as “extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly”, are considered grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions.[4] In addition to state responsibility, according to Article 146 of the Fourth Convention, such grave breaches also entail individual criminal responsibility for individuals and commanders who have committed such violations.[5]

The cases discussed in this report testifying to the wanton destruction and seizure of civilian property are also considered war crimes according to Article 8 (2) (b) (13) of the Statute of the International Criminal Court (the Rome Statute of 1988).[6] The prohibition of such breaches has been affirmed as one of the rules of customary international law binding all states, groups and individuals in international as well as non-international armed conflicts, according to Rule 50 of the (ICRC) Customary International Humanitarian Law rules.[7] The cases of pillaging and lootings discussed in this report are also considered violations of international humanitarian law according to Article 33 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, which absolutely prohibits pillage as well as reprisals against protected persons and their property. This categorical prohibition of pillaging is also based on Articles 28 and 47 of the Hague Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land in the 1907 Hague Convention.[8] Such violations are considered war crimes on the basis of Article 6 (b) of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg),[9] as well as Article 8 (2) (B) (16) of the Rome Statute of 1988.[10] The prohibition of pillaging is considered one of the norms of customary international law, binding on all states, groups, and individuals in international as well as non-international armed conflicts, according to Customary international Humanitarian Law, Rule 52.[11]

Regarding the property rights of displaced persons, Article 46 of the Hague Regulations states that “private property […] must be respected. Private property cannot be confiscated.”[12] Notably, lootings, the destruction of property and other abuses against civilians directly contributes to the continued displacement of Syrian civilians, especially in occupied territories, and in-and-of itself constitutes a violation of international humanitarian law under article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.[13] Any displacement of civilians by the occupying force would be considered a war crime in accordance with Article 6 (b) of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg),[14] as well as Article 8 (2) (b) (8) of the 1988 Rome Statute.[15]

The violations mentioned in this report, and as they have been documented by Syrians for Truth and Justice as well as “The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria”, were clearly being carried out in a widespread and systemic manner. This qualifies such violations to be considered as “crimes against humanity” as described in Article 6 (c) of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg),[16] as well as in Article 7 of the Rome Statute of 1988.[17]

Additionally, it is necessary to note that Turkey is legally obliged to respect all its treaty and customary international law obligations. Not only those relating to armed conflicts, but also all treaties of international human rights law, which remain in force even in cases of armed conflicts, including those beyond its borders, particularly in cases of occupation regarding the treatment of civilians or their property which are in Turkey’s power and under its de facto authority.

The Turkish State is therefore directly responsible for all the violations and crimes shared in this report. Turkey must put an end to crimes against protected persons, civilians, and their property in the territories it occupies. According to Article 146 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, the Turkish state is obliged, as a High Contracting Party and an occupying power, to prosecute all “persons alleged to have committed, or to have ordered to be committed, such grave breaches, and shall bring such persons, regardless of their nationality, before its own courts.”[18] Turkey must also assume its full responsibilities in protecting civilians and their property in the territories it occupies.

- Methodology

This report was jointly compiled by the organizations PÊL- Civil Waves, Hevdestî (Synergy) Association, and Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ). The report draws on a total of 24 interviews carried out by field researchers from the three partner organizations between January and September 2021. All interviews were conducted in person. Our sources include witnesses to the looting operations, locals robbed of their properties, local activists, fighters from the SNA, and officers with the Civil Police.

In addition to interviews, the report is based on verified information, including visual evidence obtained by field researchers with STJ and Hevdestî which was then corroborated by a set of testimonies compiled by PÊL- Civil Waves as part of a project documenting violations against property rights in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê.

The three organizations obtained a third set of testimonies and interviews for the purposes of verification and cross-referencing. Therefore, the third set, consisting of 10 interviews, was not quoted directly in the report’s body, and was only used to corroborate the information included herein. Among these, was the case of a man who was arrested by an SNA commander for protesting against the confiscation of a repair shop in the city of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê.

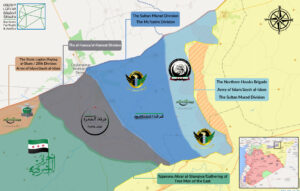

This report covers confiscations in the city of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. Using sources, researchers, and satellite imagery, the organizations created the following map delineating where various SNA factions are operating throughout Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. The factions operating under the SNA’s 2nd Legion, including the Sultan Murad Division, al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, Northern Hawks Brigade, Army of Islam/Jaysh al-Islam, and the Mu’tasim Division control the city of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and its eastern and southern suburbs. Factions operating under the SNA’s 1st Legion are stationed in the city’s western suburbs, including the U.S.-designated Tajammu Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Gathering of Free Men of the East.

Image 1- A map which displays where SNA-affiliated factions operate throughout Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê.

- SNA-Led Looting and Confiscations

A few days into Operation “Peace Spring,” the SNA-affiliated Sultan Murad Division took over the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone.[19] The zone is located east of the city and hosts over 220 shops and facilities, specialized in the trade and repair of vehicles. After they took control of the zone, the division started transferring the contents of the stores, including cars, tractors, power generators, water pumps, stored fuel supplies, and a wide range of vehicle spare parts. Later, the division sold some of the looted items back to their original owners, who risked their lives and returned to the city to check on their properties.

Pertaining to the locations of the warehouses, a field researcher with STJ reached out to three persons informed of the places where the division relocated the stolen items. The witnesses said that fighters of the Sultan Murad Division, under the command of Hamido al-Jehaishi,[20] gathered structural steel and other metals somewhere near the al-Darbasiyah road, north of the industrial zone. The witnesses added that the spot turned into a vast warehouse for looted items, as well as a station for shredding plastic pipes.

Furthermore, the witnesses claimed that the division also used a section west of the zone for storage purposes for a few months over the course of the looting operations.

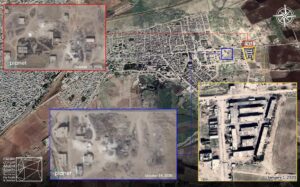

In addition to the interviews, a local source provided STJ with exclusive footage and videos, taken for the purposes of this report between October and November 2020. The visual evidence documents the warehousing operations of the looted metals and other items.

Image 2- A collage of images taken from several videos obtained by STJ, which locate the places where the division stored the looted items; some of these items appear to the right of the image.

Image 3- Satellite footage matched with live images taken from videos obtained by STJ, identifying locations where stolen items are being held by armed factions.

Image 4 – An image of the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone, taken from videos obtained by STJ.

Image 5- An image of the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone, taken from videos obtained by STJ.

Image 6- Satellite images of the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone corroborating live images taken from videos obtained by STJ.

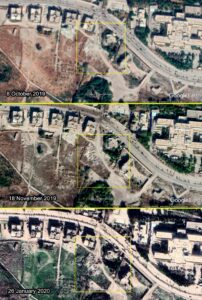

Using both video footage and exclusive satellite images, taken over several months, STJ located numerous warehouses where stolen items are being stored in the northern and western sections of the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone. The following images identify these warehouses and pinpoint their locations in the Industrial Zone.

Image 7- Satellite images of the northern and western sides of the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone which pinpoint where stolen items are being kept by armed factions.

Image 8- Satellite images of the northern section of the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone taken on different dates, identifying where stolen items are being stored.

Image 9- Satellite images of the western section of the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone taken on different dates, identifying where stolen items are being stored.

Image 10- Several the industrial zone stores, which the division looted and emptied of all contents, taken from the exclusive videos obtained by STJ.

Image 11- Piles of items looted from the industrial zone, which the perpetrators either smelted or sold to local Syrian merchants or Turkish traders, taken from the exclusive video obtained by STJ.

The testimonies compiled by human rights organizations, particularly those recorded by PÊL- Civil Waves, verify that the Mu’tasim Division also perpetrated several looting operations in the industrial zone. The interviewed witnesses told the organization that members of the division stole contents worth millions of dollars and sold the items to Turkish merchants, among others. In addition to trading in the robbed items, the fighters responsible blackmailed the assaulted stores’ owners and resold them some of their own goods.

Providing additional details on warehousing locations, the sources and witnesses said that the Sultan Murad Division runs another collection and storage facility on al-Hasakah road,[21] somewhere between the Hamdo Gas Station and the al-Amin Weddings Hall. Notably, a car bomb attacked this facility on 26 September 2020, killing five adults and a child. Among the dead were fighters of the division who administrated the facility and who operated in the ranks of an affiliated brigade called the Ahrar al-Safira/Rebels of al-Safira.

Image 12- Satellite images over several months identifying one of the possible locations where stolen items are collected along the al-Hasakah road.

After an investigation, researchers from the three organizations concluded that the perpetrators had dedicated numerous locations to storing looted items. Of these, we identified the former Cement Corporation on the al-Hasakah road.[22] Prior to Operation “Peace Spring”, the Autonomous Administration used the corporation’s facilities as a customs center in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. After the operation, fighters from the Sultan Murad Division, under the command of Hamza al-Shaker,[23] converted the center into a military station and used it to store large quantities of the stolen items, which they later sold to Turkish merchants in an exchange observed by an eyewitness, Muhammad Ali.

Image 13- Satellite images over several months identifying one of the possible locations where stolen items are collected at the site of the former Cement Corporation/Customs Center.

Muhammad Ali, 35, is based in al-Hasakah province and worked in the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone. Al-Ali returned to the zone after Operation “Peace Spring” to check on his store and possessions. To his dismay, he discovered that like many other owners he was a target for looting operations. He told the documentation team:

“I returned to Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê in November 2019, nearly a month and a half after Turkey and the factions of the Syrian National Army (SNA) controlled the city. I went to check on my store in the industrial zone, the SNA fighters had emptied it and stole all the goods and equipment I had. Furthermore, fighters of the Sultan Murad Division were stationed in the zone. They denied people access to the zone because they warehoused some of the items and metals they looted there.”

Al-Ali also gave the documentation team a first-hand account of one of the sales Hamza al-Shaker and his group carried out to dispose of the looted items in November 2019. While working to repair a power generator at the request of the group’s commander, al-Ali witnessed several transactions in which the group sold tons of stolen metal, structural steel, and scrap they stored in the courtyard of the former Cement Corporation/Customs Center to Turkish merchants.

“I was surprised to see tons of looted items stored there. While working on the generator, a grey-colored taxi with a Turkish number plate arrived at the site. There were four Turkish men in the car, hardly speaking any Arabic. I understood that al-Shaker had likely struck a deal with them earlier, because the taxi was accompanied by large trucks and cranes to load the looted structural steel and scrap and transfer them to Turkey.”

A week before he left again for al-Hasakah, al-Ali saw faction fighters take some of the metals and equipment they had looted from owners who fled the city during the offensive to an open space within the industrial zone. There, al-Ali said he watched the faction fighters sell the items, such as spare engine parts and brake pads, for paltry sums, following contractual agreements between the commanders of the Sultan Murad Division, including al-Shaker and al-Jehaishi, and Turkish merchants.

To gain additional information about the locations of the warehouses and the sales of stolen goods, field researchers with STJ reached out to Idris al-Ahmad*[24], another resident displaced from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. Al-Ahmad narrated that the Industrial High School was another location the Sultan Murad Division,[25] notably the Maimati Bash armed group, under the command of Abu al-Baraa and Abu al-Maout, used for warehousing the looted metals and scrap. Notably, the SDF had earlier converted a portion of the school into a military industrial zone.

Like al-Ali, al-Ahmad witnessed the faction collect and store the equipment and metals from the industrial zone at the Industrial school, where the Sultan Murad Division detained him for several days. Al-Ahmad recounted:

“The division had turned part of the school facility into a prison. I was held and tortured there with other people. The remaining part, which the SDF earlier used as an industrial zone, was mainly a place for collecting and smelting metals in preparation for selling them.”

Testimonies like al-Ali’s also revealed a second method factions used to sell stolen goods. While factions sometimes sold goods and signed contracts directly with Turkish merchants, in other cases they sold stolen metals and scraps to local merchants who then either sold them to Turkish merchants or transported them to areas outside Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, including Tal Abyad.

In attempt to better understand this second method, Hevdestî Association contacted a third eyewitness, who lives with his family in the Zaradasht/al-Nufus neighborhood in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. The eyewitness named several facilities that local merchants and residents—who fled other areas in Syria and settled in the region—used to store metals and industrial equipment they purchased from the commanders of SNA-affiliated factions that have been involved in looting operations. The eyewitness narrated:

“A merchant from al-Safira area, in rural Aleppo, called Abu Muhammad al-Safirani settled in our neighborhood. He converted several stores near the al-Hasakah roundabout into warehouses for collecting the items he purchased from commanders in the Sultan Murad Division.[26] These items included structural steel and water well engines, among others, which he sold to merchants from Tal Abyad.”

The eyewitness added that a second merchant, from Deir ez-Zor city, also purchased similar stolen items. This merchant stored the items in car showrooms,[27] near the Muhammad Salmo Gas Station on the al-Hasakah road. During a coincidental encounter, the merchant told the eyewitness: “If I had the opportunity, I would also buy the bricks of the houses in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. Our houses [in Deir ez-Zor] were looted during the SDF battles against the Islamic State (IS). I am here for revenge.”

The scope of the looting operations the SNA-affiliated factions carried out over the first months after Operation “Peace Spring” was not limited to the industrial zone only. Rather, armed groups from the Sultan Murad Division, led by Abu Saleh and Abu Walid Naser—both commanders within the groups of al-Jehaishi— looted equipment and agricultural vehicles belonging mostly to Syriac farmers. The two commanders targeted the Abah Agricultural Projects zone,[28] which extends over three villages, Louthi, Lazqa, and Maddba’a, as well as the surrounding villages on the Louthi- Tell Beydar. In addition to agricultural equipment, the two commanders and their fighters looted the plastic pipes of the area’s irrigation network and transferred the stolen items to the warehousing sites pictured above in the northern industrial zone.

Because the perpetrators of the documented looting operations did not concentrate their activities to specific areas, field researchers with the three partner organizations also investigated organized confiscations in the villages near combat lines, including the villages of al-Qasimiya, Umm Shfaia’a, Aniq al-Hawa, and Ba’irier, among others. In these areas, the field researchers could not document all the looting operations; however, they obtained verified accounts from eyewitnesses from these villages. The witnesses confirmed that that vehicle loaded with zinc layers, steel bars, and pieces of furniture arrived at the headquarters of the Sultan Murad Divisions in the eastern suburbs near these villages almost every day. The witnesses added that the loads were mostly stored at the division’s center in Nadas villages,[29] which the division used as their chief warehouse for construction metals and scrap in these areas.

Even though the Sultan Murad Division was the key culprit in the documented looting operations, an eyewitness based in Barqa village, in the eastern countryside of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, told field researchers with STJ that fighters from the Northern Hawks Brigade participated in stealing and dismantling vehicle engines in dumpsters or warehousing centers dedicated for looted items.[30] The eyewitness recounted:

“In Barqa village, fighters from the Northern Hawks Brigade looted the contents of three houses belonging to our families. The stolen items included 12 engines; eight Scania, two Zotye, and two Volvo, which are worth nearly 24,000 USD. Additionally, the fighters stole engine spare parts that are worth nearly 30,000 USD.”

While STJ’s field researchers covered lootings in the eastern countryside of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, Hevdestî investigated similar factional abuses in the city’s southern countryside, which al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division controls, starting from the city’s western section to the towns on both banks of the Khabur River, notably Tell Halaf, Duaira, al-Manajir, al-Ameriya, as far as the two villages of Lilan on the international highway and al-Arisha on Ras al-Ayn-al-Hasakah road. Hevdestî spoke to an eyewitness based in Tell Halaf, who said that after Operation “Peace Spring”, fighters of the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, under the command of Seif Abu Baker, looted water well engines, irrigation pipes, electric and industrial equipment from the town and nearby villages, including Qitina, al-Nasiriya, Duaira, Shallah. The eyewitness added that the fighters collected and stored the looted items in Khan Kabir on the Tell Halaf-Mabrouka road before they sold them to local or Turkish merchants.

- Looted Items Sold to Original Owners

When the Turkey-led Operation “Peace Spring” abated, numerous Arab, Kurdish, Syriac, and Armenian original inhabitants who fled the area during combat returned to the city to check on their properties, particularly because they heard that the military activities were accompanied by large-scale and organized looting operations.

PÊL- Civil Waves met one of the city’s residents who returned after the operation ended. The eyewitness, Abu Muhammad. He described the city’s landscape and the faction’s activities at the end of hostilities:

“In November 2019, I returned after the battles ended and the city was occupied. The city was a home for ghosts, fear, and horror. I heard of the thefts and looting in the industrial zone and that armed opposition groups were reselling some of the stolen items to their owners. This is what motivated me to return to the city; I hoped that I could buy my own possessions from them.”

Abu Muhammad said that he struck a deal with an influential member within the Sultan Murad Division. The fighter, who was based in the Zaradasht/al-Nufus neighborhood, helped Abu Muhammad collect his remaining goods from the Industrial Zone. Abu Muhammad recounted:

“When I visited my store, I was surprised that most of the goods were stolen, especially pricy spare parts. The perpetrators left only used or large parts. I purchased the remaining contents of my store. Gunmen brought me these items to the Zaradasht neighborhood, under the protection of fighters from the Sultan Murad Division. The items they sold me barely amounted to 10% of what I had in my store.”

PÊL- Civil Waves interviewed another returning resident. Jihad*, a former resident of Ronahi/al-Kharabt neighborhood, told PÊL researchers what happened to the engine oil store and the restaurant he had in the industrial zone. He narrated:

“There were goods worth about 90 million Syrian Pounds (SYP) in the store when Turkish forces invaded the area. Both the store and the restaurant I had were cleared of all their contents. Nothing was left.”

In addition to his properties in the industrial zone, Jihad became a victim of lootings that targeted residential neighborhoods. Armed opposition groups looted his house in Ronahi neighborhood, even taking the doors and windows, as Turkish forces stole the contents of his sand and gravel washing plant. Turkish forces looted nearly 2500 square meters of sand and all the equipment they found on the premises. In addition to these losses, Turkey-backed armed opposition groups confiscated Jihad’s agricultural land and invested in it.

Fares Abdulaziz Khalaf, currently based in Qamishli/Qamishlo city, is a third eyewitness and a victim to factional looting. Khalaf owned a large two-story agricultural tractor store and three massive warehouses. Khalaf told PÊL- Civil Waves that most of the stores in the industrial zone were run by Kurdish owners:

“Before I was displaced, I used to live in Zaradasht neighborhood, and I worked in tractors and water pumps trade for over 25 years. I am quite familiar with the industrial zone, which included about 220 stores, owned by several ethnic components, mostly Kurds, who owned nearly 75% of the stores. There were also Arab and Christian Syriac owners.”

Khalaf’s store, where he also sold water pumps, was looted by Turkey-backed armed opposition groups. He recounted to PÊL- Civil Waves how the factions stole his possessions and relocated them to another region:

“One of the neighbors saw my goods being stolen. He told me that they [fighters of armed opposition groups] brought two locomotives and a big crane to load the items. The neighbor also told me that a group of masked gunmen guarded the place while my belongings were loaded in vehicles. Later, other people told me that they found tractors and vehicle parts that I sold at my store in Tal Abyad. Apparently, Tal Abyad is the place where the fighters relocated the stolen items.”

In addition to the store, the perpetrators looted Khalaf’s two-story house. The fighters stole the house’s contents, unhinged the doors and windows, and ripped electricity extensions from walls. Khalaf added:

“Currently, members of the Sultan Murad Division live in my house. They seized it. One person told me that the Northern Hawks Brigade was present in the neighborhood during the theft and looting, and they had headquarters in a house they seized, which originally belonged to a man called Mastou Yazidi.”

STJ, for its part, obtained information that a merchant from the Safira city, in rural Aleppo, purchased a significant portion of the items looted by armed opposition groups.

PÊL- Civil Waves interviewed a fourth store owner, who returned to the city after the ceasefire that put an end to Operation “Peace Spring.” Raizan* lived in the Zaradasht/al-Nufus neighborhood and returned to Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê city on 25 October 2019. He told PÊL- Civil Waves that the inquiries of the factions’ checkpoints at the city’s entrance were mostly focused on Kurdish residents:

“When a ceasefire was announced, I headed to the city with my sister-in-law’s husband. At the first checkpoint, set up at the city’s entrance, the fighters were particularly inquiring about Kurdish residents…When I arrived at the city, I immediately went to the industrial zone to check on my store. The goods at the store were untouched, but my warehouse’s contents were completely looted.”

Raizan told PÊL- Civil Waves that fighters from the Mu’tasim Division looted the items he kept at the warehouse. He added that the fighters also blackmailed him, requesting 3,000 USD to return his belongings:

“I paid them the money they requested, on the condition that I would be returned my goods the next day. However, the next day, I learned that I was a victim of fraud by one of the division’s fighters. When I went to get back the stolen items, the person I negotiated with disappeared.”

Desperate to get his possessions back, Raizan visited his store in the industrial zone again on 29 October 2019. There, he found out that fighters from the Mu’tasim Division had been stationed in the store and asked him to pay 10,000 USD in return for his store’s contents. After negotiating with them, the fighters ultimately accepted to sell him his own goods for 5,000 USD.

After purchasing back his goods, Raizan told PÊL- Civil Waves that he left Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, and after his traumatizing experience, does not plan on returning so long as armed opposition groups continue to occupy the area.

To further investigate looting operations in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, PÊL- Civil Waves interviewed a technician who repairs vehicles and lives in the Zorava/al-Hawarneh neighborhood. The technician returned to the city in November 2019, which he left due to Turkish hostilities, and was devastated to discover that SNA-affiliated factions had looted all his belongings. He narrated:

“I owned two apartments, a store in the industrial zone, and four plots of land, on which we were planning to build residential units, and three dunums of agricultural land. The gunmen stole all my house’s contents. They also denied me access to the house when I was visiting the city because they had turned it into a warehouse for storing ammunition. As for my store, the door was broken and the items inside were all gone. I believe that the store is no longer usable.”

The witness accused the Sultan Murad Division of looting his properties, particularly the items in the industrial zone facility because, he says, he saw some division fighters near the store when he went to check on the property.

Similarly, Abdullah Yousef* escaped his house in the Zaradasht neighborhood in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê during the Turkish invasion. Today, he lived in al-Hasakah city.

Even though he was away from home, Youssef kept in touch with his neighbors to check on his properties. However, he decided to return to the city on 10 November 2019. He told PÊL- Civil Waves about the extortion he and other visitors experienced at the hands of the personnel at the checkpoint established at the city’s entrance:

“At the first checkpoint, set up at the al-Aliya area, there were members from the Turkish army and Syrian armed groups. They asked us for 5000 SYP each to allow us to enter the city. The city was completely depopulated. When I entered, I first visited the industrial zone to check on my store and then headed to my house. My house had been looted.”

Youssef added that while he managed to return home, opposition groups denied him access to his store in the industrial zone. While in the city, he befriended a fighter from a nearby headquarters, who claimed he had come from Bab al-Hawa city. After negotiations, the fighter agreed to collect the contents of Yousef’s store and bring him to the industrial zone for 1,000 USD.

“I had to accept [the fighter’s] offer because the goods I had in the store in the industrial zone were worth a lot. The fighter went to the industrial zone and shot a video of the store and its contents; I was surprised to see that half the items were stolen. Later, I accompanied the fighter into the industrial zone. I was shocked at the sight — the majority of the zone’s stores were looted, and their contents were stolen.”

Ultimately, Youssef rescued his store’s remaining goods after he paid the fighter 150,000 SYP for bringing the goods outside the zone and an additional 2,500 USD for helping him pass the items through military checkpoints, run by the Turkish or SNA forces.

Youssef was not the only owner asked to pay factions money in exchange for his belongings. PÊL- Civil Waves interviewed Ramadan Ali*, who was blackmailed for his goods by fighters with the Sultan Murad Division. Ali narrated:

“I left all my belongings behind when I escaped the Turkish offensive in the city. When I returned to the industrial zone to check on my store, I was taken aback by the situation. Most of the goods and equipment were stolen. Fighters from the Sultan Murad Division asked for a huge sum of money in exchange for returning me the items that were already mine. There was this person, called Hamza Shaker; he was in charge of the zone on behalf of the division. Most likely, all the looting operations and then relocation of the stolen items were carried out under his supervision.”

Likewise, Hussein Ahmad*, born in 1981, owned a store for spare vehicle parts in the industrial zone. Like the other witnesses, Ahmad was displaced from the city during the Turkish hostilities. When he returned, he was horrified by the extent of thefts in the industrial zone. He told PÊL- Civil Waves:

“After Turkish forces and their affiliated [Syrian] factions controlled the city, I risked my life and headed home. I stayed there for 10 days. I visited the industrial zone and saw how all the stores were forcefully opened and most items were stolen. Fighters from the Mu’tasim Division, which controlled the section of the zone where my store was located, took me to the store. My store was completely empty of contents that were worth approximately 150,000 USD. They did not give me my store back and, thus, I left the area devastated.”

Ahmad said that the Sultan Murad Division was also responsible for home seizures, which targeted his house and a dozen others in the Zaradasht neighborhood. Furthermore, he confirmed that the division housed Arab families, coming from other Syrian areas and with whom they were acquainted, in some of these houses, while they turned the rest into military centers. Ahmad stressed that the fighters he saw had uniforms that displayed the name of the Sultan Murad Division, as well as tags in the shape of the Turkish flag and the opposition’s green flag, the independence flag, on their shoulders.

Another witness, Jumaa Daoud Ma’ai, a father of seven who owned a vehicle parts store and electrical appliance shop in the industrial zone, told PÊL- Civil Waves that he received calls from an SNA fighter regarding his properties in the city:

“After I escaped the city, a member from the armed groups called me saying he was an SNA fighter. He asked me to return to the city and literally said: ‘Your store is still full of items; we found 300,000 SYP in the drawers, in addition to the party’s ID.’ He was referring to the merchant ID that the Autonomous Administration granted to merchants in the industrial zone.”

Ma’ai said he was reluctant to return to the city, frightened by stories he heard about atrocities committed by the SNA organizations. However, he received photos of his store from a friend who returned which he then shared with PÊL- Civil Waves. The images show the store burned and looted.

Ma’ai said that he received a second call from fighters with the armed opposition groups, in which they referred to his electrical appliances shop. He recounted:

“My appliance shop was full of German electric devices that were worth an estimated 200,000 USD. The gunmen who called me, said: ‘We will sell you big devices for 100 USD each, and smaller ones for 50 USD.’ However, I refused to go there, fearing death. I lost all my belongings in the industrial zone, which were worth nearly 800,000 USD, not to mention the houses and other real properties I was deprived of.”

Image 14 – Photos provided by Jumaa Daoud Ma’ai of his store before and after being burned and looted by armed SNA factions.

- Looted Items Sold to Local and Turkish Merchants

According to information provided by eyewitnesses, among them workers from various departments operated by the local council, armed factions sent vehicles loaded with structural metals, including steel and brass, as well as scrap they looted from the Ras al-Ayn Industrial Zone to the city of Tal Abyad almost every day. The witnesses added that the factions’ commanders sold most of the looted items to local or Turkish merchants, through unmediated deals. One of the witnesses, an officer with the SNA’s Free Police, narrated:

“Every day, large quantities of the looted items, including metals and other goods, passed the checkpoints within and around the city. However, we, the police officers, could do nothing about the shipments; we could not stop cars or trucks, because the Turkish Gendarmerie forces ordered us not to obstruct the passage of any truck that presented them with a mission document, or an access permit issued by the Military Police.”

Field researchers with STJ obtained evidence that the looted metals’ sale deals were not carried out exclusively by the SNA factions. The researcher tracked one sale operation of metals stolen from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. Another eyewitness said that the Ras al-Ayn Local Council was a party in this deal:

On 11 August 2020, a checkpoint operated by the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division in Tell Halaf, commanded by Sanad Abu Hamdan, stopped several trucks loaded with aluminum alloys, scrap, and electricity cable reels. The trucks were headed to the city of Tal Abyad. Investigating the matter, the checkpoint learned that the shipment belonged to a commander within the Sultan Murad Division, called Hamza Shaker, who had a deal with a Turkish merchant. Shaker was supposed to deliver the merchant the goods in Tell Halaf, from where the merchant would transport the goods to Tal Abyad and next to Turkey. The checkpoint confiscated the shipment and relocated it to the facility of the Automated Bakery in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. [31]

The sources interviewed for this case said that the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division and the Sultan Murad Division are engaged in constant disputes over control of the city’s resources. The sources added that the local council, for their part, are advocating for expanding the dominion of the Aharar al-Sharqiya faction.

Sources informed field researchers about the fate of the seized shipment. They recounted those seven trucks arrived into the courtyard of the bakery in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. On 27 August 2020, the local council unloaded the contents of three trucks only and made a deal with the Sultan Murad Division and the Governor of Şanlıurfa, Abdullah Erin, that allowed[32] the division to retain the remaining four trucks. Regarding the deal, field researchers with STJ contacted a worker from the local council. The worker narrated:

“A few days after the three trucks were unloaded in the courtyard of the automated bakery, the goods disappeared, and no one had an idea about what happened. Later, we discovered that the local council had sold the goods to a local merchant based in Tal Abyad city in exchange for 41,000 USD.”

The source added:

“The former head of the local council, Mari’ al-Youssef, told us that the confiscated metals were sold to a Turkish merchant and that the Turkish governor was informed of the sale operation. The official also said that the money from the operation will be used to cover the expenditures and needs of the city.”

- Electricity Transformers Looted and Sabotaged

The factional looting operations in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê were not limited to the industrial zone. The involved factions, notably Sultan Murad Division and al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, looted and sabotaged the city’s electricity and irrigation networks and rendered both inoperable. Fighters from the factions robbed the electricity cables and transformers, as well as the water pumps and pipes from the city’s suburbs. To obtain additional details on this case, a field researcher with STJ interviewed an electrician who worked for the local council. The source said:

“In Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê city, 30 electricity transformers were looted, all large with the capacity to generate 400 to 100 watts. In the city’s suburbs, over 20 transformers were stolen.”

A different eyewitness, Abu Omar*, said that fighters from the al-Muwali armed group, affiliated with al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division and consisting of members from the al-Muwali tribe, looted eight transformers, with 1000 W capacity, in addition to eight water pumps from the Hasou Mashkini agricultural wells, which are located in the tringle of the villages of al-Madina, Tal Manda and Abdulsalam. The looted items were all relocated to an unknown area.

In Ba’irier village, fighters from the group led by Abu Abdo Safira, affiliated with the Sultan Murad Division, looted five electricity transformers and one water pump.

Providing an account on similar thefts in Louthi village, a witness said:

“After Operation Peace Spring, nearly two months after they controlled the area, the armed group led by Abu Hassan al-Majed, affiliated with the Sultan Murad Division, looted the cables of the village’s water pumps and electricity transformers. The locals paid more than a million SYP for only the stolen electricity cables, while they continue to suffer from the unserviceable water wells.”

In the three villages of al-Qasimiya, al-Aziziya, and Abdulsalam, a witness said that fighters from the Sultan Murad Division looted the electricity cables of the transformers and overhead power lines, as well as water pumps. The witness added that fighters from the Mu’tasim Division also participated in the thefts.

For their part, fighters from the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division perpetrated all the metal looting, collection, and transportation operations in the villages of Umm al-Asafir, al-Arisha, al-Manajir, and al-Salihiya. The fighters operate under the command of Abdullah Halaweh, an SNA lieutenant and deputy commander of the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division. Regarding these looting operations, witnesses said that the fighters sabotaged a number of buildings in al-Amiriya village as they dug to extract structural metals.

In the city’s western countryside, a worker with the Syrian Civil Defense, also known as the White Helmets, told field researchers with STJ that fighters from the armed group led by Abu Jamou, a commander within the ranks of the Tajammu Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Gathering of Free Men of the East, looted irrigation pipes and equipment, and electricity transformers and structural metals from the projects run by the Syrian-Libyan Company, which is headquartered between the cities of Mabrouka and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. The projects extend over large swathes of agricultural lands and include numerous modern agricultural vehicles.

Armed opposition groups also looted the electricity transformers and equipment of the Mabrouka Power station,[33] which is located on the M4 International Highway and 14 kilometers from the town. Documenting the theft, a field researcher with STJ field researcher contacted a farmer who works on agricultural land near the station. The farmer narrated:

“Sometime after mid-October 2019, an opposition armed group stationed themselves at the power station. I do not know their exact name. After they settled in the area, many locals saw the group’s fighters transport large quantities of brass they extracted from electricity transformers they damaged. Additionally, the fighters looted some of the equipment they found at the station.”

STJ previously published a detailed report on the looting of equipment from the Mabrouka Power Station. The perpetrators were from al-Safwa Islamic Battalions. The Al-Safwa Division is a coalition of extremist Islamist factions that merged in April 2016 and operates primarily in Aleppo and its northern countryside. The coalition includes the battalions of Minhaj al-Sunnah, Rijalu Allah, Mecca, al-Quwa al-Muwahida, Youssef al-Halabi, al-Ansari, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, al-Handasa, and Seif Allah.

- Farmlands Destroyed by Steel Looting

After taking control of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, fighters with the Sultan Murad Division, operating within a group led by Commander Abu Meri’, began extracting the steel from a network of steel-enforced tunnels dug by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) beneath farmlands in the villages of al-Twaimiya and Ayn Hisan. Eyewitnesses and local sources claimed that Sultan Murad Division has been digging for steel as late as 2021.

While in control of the area in 2018 and 2019, the SDF established a network of tunnels, reinforced with steel and covered by asphalt, across the area surrounding the villages of Tal Arqam, al-Sufr, al-Duaira, and al-Shirka. A second network of tunnels stretches as far as the Kashto village, in addition to the dense tunnel network within the city’s neighborhoods, including al-Mahatta al-Shamali, al-Ibra, Ronahi/al-Kharabat, and Zorava/al-Hawarneh, as well as within its northern section and the western suburbs of the al-Aziziya village, which cover plots as far as al-Rawiya village.

When the Sultan Murad Division took control over the area, they began pulling the steel from the tunnels — damaging the farmlands in the process. One witness, Aziz, said that the steel the SDF used in the original construction of the tunnels was manufactured in two steel centers in the villages of al-Safeh and Hawsh al-Rai.

“The tunnel steel the faction fighters are working to extract amounts to thousands of tons. To my knowledge, the steel manufacturing center in al-Safeh alone consumed at least two and half tons of steel every day for a year to scaffold and support the tunnel networks south of Ras al-Ayn. Namely, the center used approximately 1000 tons throughout the year, with non-working days included.”

The eyewitnesses interviewed regarding steel thefts said that the digging work damaged the farmlands lands that hosted the networks, because the fighters had to dig as deep as 10 meters along the tunnel to reach the steel. The witnesses added that fighters often left the digging sites open, did not fill the holes, or remove the asphalt rubble resulting from the demolitions.

To read the report in full as a PDF (31 Pages), follow this link.

[1] Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907, Art 42.

[2] The Geneva Conventions of 1949.

https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/publications/icrc-002-0173.pdf

[3] Ibid., GC IV, Art. 49.

[4] Ibid., GC IV, Art. 147.

[5] Ibid., GC IV, Art. 146.

[6] The Rome Statute of 1988, Art. 8 (2)(b)(xiii).

https://www.icc-cpi.int/resource-library/documents/rs-eng.pdf

[7] ICRC, Customary IHL Database, Rule 50.

https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/ara/docs/v1_rul_rule50

[8] Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907. Art. 28 and 47.

[9] Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg), Art. 6 (b).

[10] The Rome Statute of 1988, Art. 8 (2)(b)(xvi).

https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/publications/icrc-002-0173.pdf

[11] ICRC, Customary IHL Database, Rule 52.

https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/ara/docs/v1_rul_rule52

[12] Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907, Art. 46.

[13] The Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, Art. 49.

https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/publications/icrc-002-0173.pdf

[14] Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg), Art. 6 (b).

[15] The Rome statute of 1988, Art. 8 (2)(b)(viii).

https://www.icc-cpi.int/resource-library/documents/rs-eng.pdf

[16] Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg), Art. 6 (c).

[17] The Rome statute of 1988, Art. 7.

https://www.icc-cpi.int/resource-library/documents/rs-eng.pdf

[18] The Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, Art. 146.

https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/publications/icrc-002-0173.pdf

[19] According to testimonies obtained by PÊL- Civil Waves, the Mu’tasim Division also participated in looting operations. However, its actions were comparatively minor to the thefts and seizures carried out by the Sultan Murad Division.

[20] According to information obtained by STJ, Hamido al-Jehaishi is one of the commanders in charge of the Sultan Murad Division’s fighter groups and is known for maintaining close ties with the Division’s chief commander Fahim Issa. Furthermore, al-Jehaishi was among Syrian mercenaries sent to fight in Libya alongside the Government of National Accord, led by Fayez al-Saraj, against the Libyan National Army, led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar. In Libya, al-Jehaishi commanded several military fronts during several confrontations.

Additionally, the testimonies collected by STJ confirm that al-Jehaishi participated in several looting operations in Libya. Moreover, under the mantle of the division, he also engaged in pillage and looting operations of properties in a neighborhood in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. The targeted neighborhood, which is located near the Grand Mosque, hosts the home of the source who relayed this information to STJ.

[21] The coordinates of the storage facility operated by the Sultan Murad Division: 36.8301542, 40.0886902

[22] The coordinates of the former Cement Corporation the division used to store looted items and metals: 40.080287, 36.840743

[23] According to information obtained by STJ, Hamza al-Shaker is a commander of a military group, who carried out the larger part of looting operations across Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. Additionally, the group confiscated the properties of internally displaced people, particularly the original inhabitants of the area, and engaged in violent clashes with other armed factions, notably al-Hamza/al-Hamzat, over their shares of the seized houses.

Testimonies collected for the purposes of this report also confirm that al-Shaker housed the fighters of his own groups and their families in the confiscated houses. As for shops, these the group either used to sell stolen furniture and other looted items or offered for rent.

[24] * This mark connotates the use of a pseudonym used to protect the safety of our sources.

[25] The coordinates of the Industrial High School facility: 36.846511, 40.078875

[26] The coordinates of the warehouses near the al-Hasakah roundabout in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê: 36.844963, 40.077304

[27] The coordinates of the car showroom near the al-Hasakah roundabout in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê: 36.844715, 40.077567

[28] The coordinates of the Abah Agricultural Projects Zone: 40.2214622, 36.8424173.

[29] The coordinates of the Sultan Murad Division’s headquarters in Nadas village: 36°51’41″N 40°10’53″E.

[30] The Northern Hawks Brigade operates within the 2nd Legion of the SNA, 22th Division, under the military title Liwa 224/ 224th Brigade. The Brigade was established in September 2012 in Mount Zāwiya, in Idlib, by Hassan Hajj Ali, known as Hassan Khayriya. The faction has manpower of approximately 2500 fighters, who fought along other armed opposition groups during operations, the “Euphrates Shield”, “Olive Branch”, and “Peace Spring.” These fighters are stationed in the eastern countryside of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê city.

[31] The coordinates of the automated bakery: 40.079618, 36.848162

[32] After Operation “Peace Spring”, Turkey assigned the provincial departments in the state of Şanlıurfa with the task of overseeing the service and administrative affairs in the two cities of Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê.

[33] The Mabrouka Power Station was later repaired by the Syrian government.