Introduction:

The al-Sultan Family, who hails from the west countryside of Tall Tamer Town, endured a horrific tragedy as members of the opposition Syrian National Army (SNA) executed one of their sons in plain view of his mother on the eve of Eid al-Adha (Feast of Sacrifice). The mother was detained, and one of the victim’s uncles was arrested and tortured for demanding the recovery of the body.

According to the testimonies collected by Synergy, the victim Abd al-Sultan, 39, was driving his mother to visit a relative when a patrol of the SNA forces intercepted them on the M4 Highway. The SNA members attempted to confiscate Abd al-Sutlan’s vehicle, but he objected. After a brief argument, the members shot him dead in front of his mother and then took his body and his mother to the Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê Hospital. His mother was later released but was not permitted to bury her son.

Three days later, Salih al-Sultan, the victim’s uncle, arrived in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê to demand the body. However, five members of the Military Police forces beat him severely and arrested him on charges of dealing with the Autonomous Administration. He was denied medical treatment and the right to retain an attorney.

20 days passed before tribal dignitaries could reach an agreement with leaders of the SNA-affiliated Military Police and the Civil Police, allowing for handing over Abd al-Sutlan’s body to his family for a decent burial in return that the story was to be kept confidential. The uncle was released after paying a ransom of 6,500 USD.

The story of al-Sultan Family exemplifies the ongoing violations that the local people experience at the hands of the SNA forces in areas of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, Tall Abyad/Girê Spî, and Afrin, where Turkey claims are “Safe Zones” for the Syrian refugees to return to, despite repeated confirmations from the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (COI) that these areas remain unsafe. Human Rights Watch has (HRW) also confirmed that these zones have historically been unsafe, and that they are demonstrably among the most dangerous places in the country.

During the first half of 2024, Synergy documented the arrest of 338 persons (including eight children and 21 women, two of whom are women of special needs) by the SNA’s factions in areas of Afrin, Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, and Tall Abyad. Turkish forces were also involved in committing at least 40 of these arrests.

231 victims, among them a man and two women with special needs, whom Synergy have documented their arrest stories remain forcibly disappeared in the SNA-run prisons in Afrin, Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, and Tall Abyad/Girê Spî. Meanwhile, 107 persons were released; the majority of them survived after their families were compelled to pay financial ransoms to leaders and members of the SNA.

These violations reflect the ongoing state of insecurity and instability in the Turkish-occupied areas in northern Syria and the absence of justice and accountability. The lack of effective remedy mechanisms for the victims means that the perpetrators and violators remain beyond accountability, thus encouraging the commission of these violations, in light of the judicial system’s inability or unwillingness in those areas to address these transgressions fairly and effectively.

The SNA conducted no investigations in its forces’ practices, which continue to arrest civilians ensuing them forcibly disappeared persons and violating their rights, nor did the Turkish government that has effective command and control on these forces to change their arbitrary conduct. On the contrary, it appears, in some cases, that the Turkish government was involved as a partner in committing such violations.

Therefore, the Turkish military commanders are held criminally responsible for violations committed by the SNA factions in instances where the Turkish leaders knew or should have known about such crimes or failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures to prevent their commission.

As an occupying power, the Turkish authorities must ensure that their own officials and those under their command in the SNA do not arbitrarily detain or mistreat anyone. The Turkish authorities are also obliged to investigate alleged violations and ensure that those responsible are appropriately punished.

Overall, the reiteration of these incidents reflects the existence of a suppressive environment that does not encourage a voluntary and safe return of the internally displaced persons or enforced migrants to their Turkish-occupied territories, resulting in constant displacement and social instability in the region.

Escalation of Arrests in the Turkish-Occupied Territories:

During the first half of 2024, Synergy Association documented the arrest of at least 203 persons (including 13 women and eight children) in Afrin Region and its surrounding towns. Out of them, only 33 arrestees were released while the fate of 170 is still unaccounted for. On the other hand, in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tall Abyad/Girê Spî and their countryside, Synergy documented the arrest of 135 persons, including eight women. Of these, 74 arrestees were released while the fate of 61 others remains undisclosed.

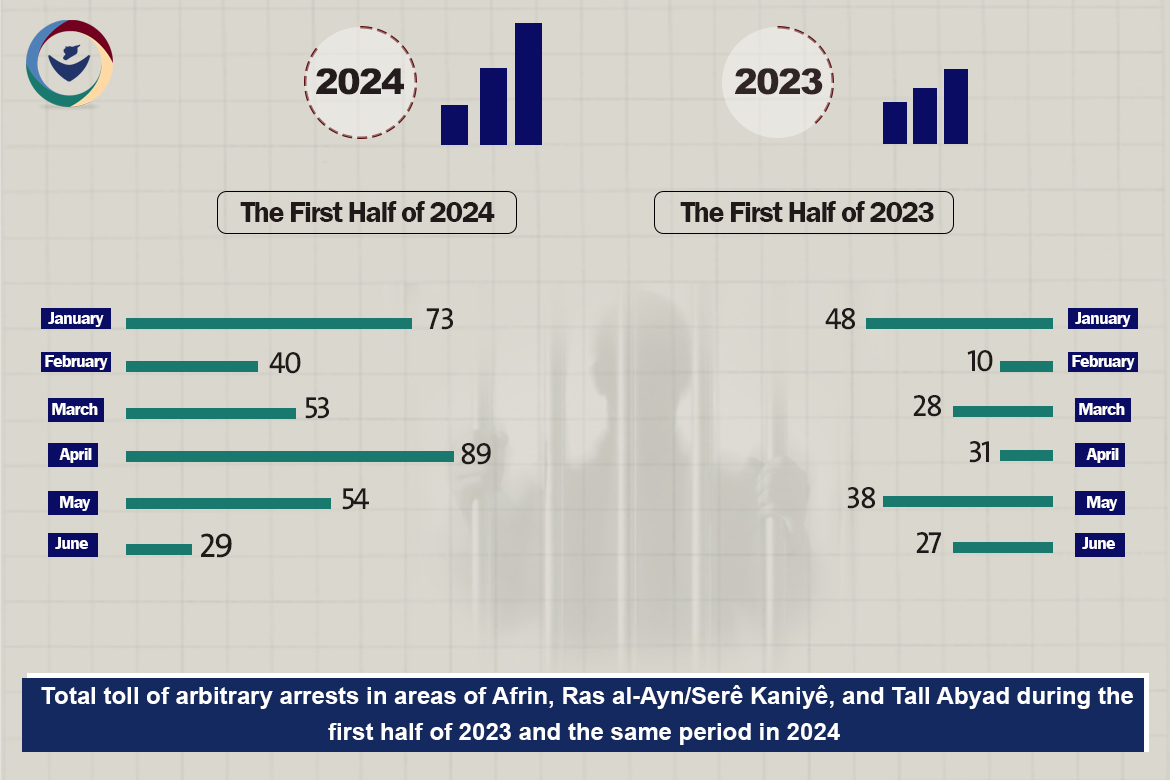

Comparing the first half of 2023 to the first half of 2024, it can be noted that arbitrary arrests in areas of Afrin, Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, and Tall Abyad/Girê Spî have almost doubled. The arrests rose from 182 cases in the first half of 2023 to 338 cases during the same period in 2024.

The perpetuation and escalation of arbitrary arrests in the SNA-held areas, with the support of Turkish forces, further complicates the security situation and deepens suffering of the local people, specifically the returnees.

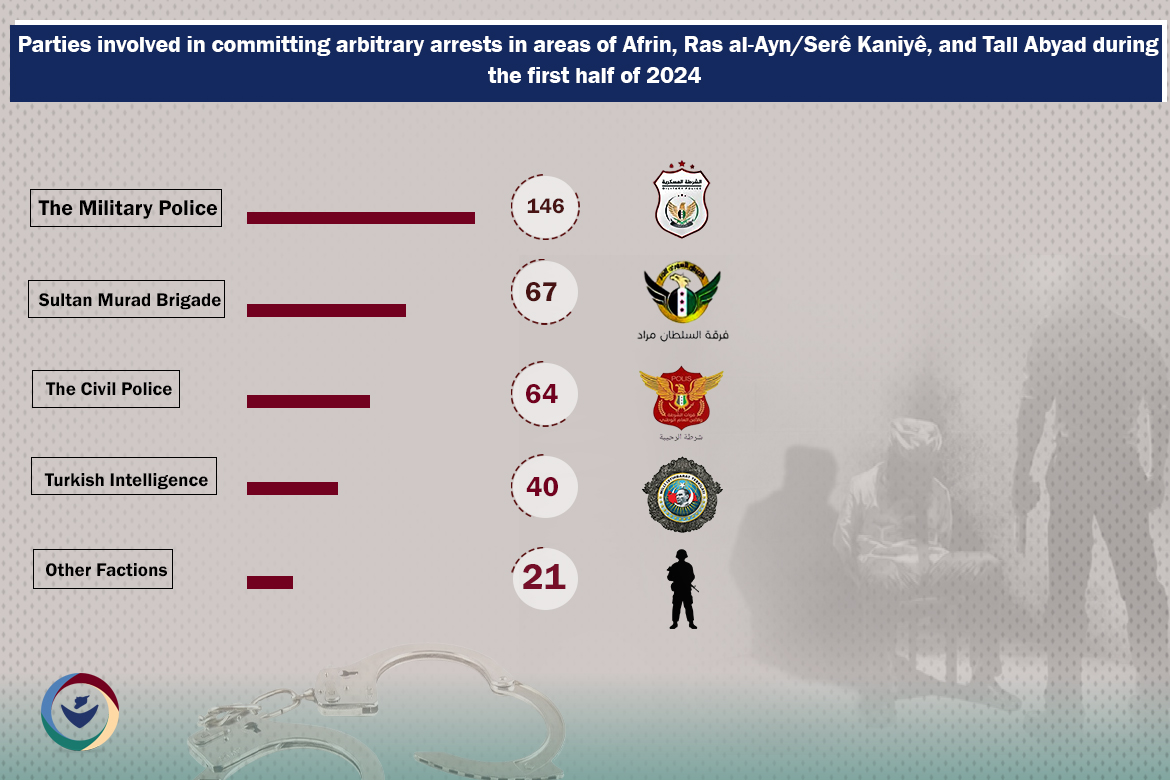

According to Synergy’s analysis of documented information on arbitrary arrests in Afrin, Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tall Abyad, forces of the Military Police were involved in 146 arrest cases, followed by the Sultan Murad Brigade with 67 arrests and forces of the Civil Police with 64 arrests. Furthermore, the Turkish intelligence carried out 40 arrests. Other factions within the SNA, such as al-Hamzat Division, Sultan Suleiman Shah (al-Amshat), Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Gathering of Free Men of the East, were also implicated in other arrest incidents. Moreover, it has been confirmed that at least six detainees were transferred to Turkey.

Synergy Association relied in its documentation process on the information collected in its database provided by a network of field researchers, and on information and details provided by the detainees’ families and eyewitnesses. Furthermore, it verified the information through publicly available sources (open sources).

Synergy Association notes that violations committed by Turkey and the SNA-affiliated factions in Afrin, Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tall Abyad regions are far more than what have been documented and verified by name, surname, date and place of arrest. As the Association believes that the actual number of arrest cases is significantly higher than the figure presented in this report.

Detention as a Recurring Pattern and a Widespread Systematic Practice:

The motives behind the majority of detention and deprivation of liberty operations in areas of Afrin, Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tall Abyad/Girê Spî were to extort the victims and their families to get financial ransoms or for intimidation purposes to push them to leave the area. Some civilians, including a man and two women with special needs, were arrested by Sultan Suleiman Shah (al-Amshat) for demanding the return of their properties. They are still in custody.

Moreover, Synergy documented cases of arresting some asylum seekers, who endured torture and cruel treatment by the Turkish Border Guards (Gendarmerie) before being handed over to forces of the Military Police in the SNA. The fate of 36 arrestees, among the 145 asylum seekers documented by Synergy as arrested throughout the reporting period, remains unaccounted for.

Synergy has also documented four cases, where relatives of the detainees were forced each to pay 2,900 USD for their release, whereas in one instance, an asylum seeker’s personal belongings in addition to 1,500 USD were looted. In the case of handing over the body of Abd al-Sultan to his family and the release of his uncle, Salih al-Sultan, an amount of 6,500 USD was paid to the Military Police and the Civil Police. There were other four documented cases, in which families of the detainees were asked to pay each 30,000 USD, and due to their inability to pay, the detainees remain arrested and forcibly disappeared.

Within the context of these arrests, it is important to note that the Turkish intelligence oversees, or at least has extensive knowledge of the process of arrest and enforced disappearance, as well as the types of torture accompanying them. “Ongoing abuses including torture and enforced disappearances of those who live under Turkish authority in northern Syria will continue unless Turkey itself takes responsibility and acts to stop them,” said Adam Coogle, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch (HRW). HRW’s report, “Everything is by the Power of the Weapon”, confirms that “the Turkish Army and the Turkish intelligence agencies are involved in implementing and supervising the violations.”

According to an intelligence briefing published in December 2022, by New Lines Institute, “the Turkish military and intelligence officers heading these centers [Afrin and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê] coordinate the distribution of ongoing military responsibilities, make all decisions, and inform the Syrian commanders [SNA commanders], who then carry out the orders.” Synergy documented no less than 22 arrests carried out by Turkish intelligence forces since early 2024.

The continuing, recurrence, and escalation of arbitrary arrests in these territories affirms that these practices are not isolated or random incidents, rather, they are part of a widespread systematic pattern. These ongoing violations clearly refers to a suppressive systematic policy, aiming to intimidate the locals, particularly the Kurds, and forcing them to leave their original places of residence, or reluctantly accepting financial extortion in exchange for their freedom.

Torture and Ill-Treatment:

A military source within the SNA informed Synergy that they witnessed the arrest of approximately 50 people at the hands of Sultan Murad Brigade, as they attempted to enter Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê with intentions to cross into Turkish territory. 44 persons from the group were released after they altogether paid 13,200 USD to the Brigade, while the remaining six were kept in custody, accused of dealing with the Autonomous Administration/the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). According to the witness, interrogation with the detainees was accompanied by various forms of torture, including beating, kicking, punching, and beating with cables, in addition to psychological harm, such as verbal abuse and humiliation.

Apparently, dealing with the Autonomous Administration/the SDF remains the most common accusation pointed against the detainees in the Turkish-occupied territories. The witness confirmed that two, out of the six detainees, are Arabs from Syria, not from the SDF-held areas. He added that the six were attempting, along with the others, to cross to Turkey illegally, aiming to travel onwards to Europe.

Documented patterns of torture and ill-treatment committed by the opposition SNA reflect the methods the Syrian government implements in its different security branches. The interviewees detailed different forms of torture they endured or witnessed while they were in prison. The detainees were beaten with sticks, hosepipes and electricity cables, in addition to slapping, kicking and punching.

Several victims were subjected to Blanco (shabah) and Farouja (chicken) methods of torture, and had cigarettes extinguished on their bodies. While others were suspended from the ceiling and beaten by the butts of guns and electrocuted. Other patterns of torture included drowning, breaking fingers, making wounds using sharp objects, and being dragged behind a military vehicle.[1]

Physical torture was accompanied by psychological harm as well. The majority of the victims were subjected to humiliation, while some were compelled to witness other individuals being tortured more severely and were threatened with the same punishment if they did not cooperate and confess the information needed. Many victims were threatened with death, and firearms were pointed towards the heads of some. Several ended up agreeing to sign confessions they never made.

It should be noted that Turkish officials were present regularly in SNA-run detention facilities. Former detainees stated that Turkish officials were also present during interrogation sessions, in which torture was used, indicating that the Turkish Army and Turkish intelligence agencies are involved in implementing and supervising these violations.

A joint report published by Synergy Association for Victims on June 26, 2024, titled “In the Absence of Accountability: Torture as a Systematic Policy in Northern Syria”, documented that torture and ill-treatment by the SNA-affiliated factions amount to be part of a widespread systematic pattern, aiming at intimidating the locals, especially the Kurds, and pushing them to leave their original places of residence, or continuously submit to financial extortion. The report was based on the analysis of 65 interviews with victims, survivors and their families in areas of Afrin, Ras la-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tall Abyad.

Inhuman Detention Conditions:

The Turkish-backed SNA did not adhere to any minimum standards that should be applied to individuals detained by its forces. All of the interviewees reported being held in overcrowded places or solitary confinement cells for prolonged periods without any justifications. Inhumane detention conditions were imposed on all the victims, in which the perpetrators aimed to either increase pressure on the victims to extract confessions, information, and ransoms from the family, or without any specific purpose, just to cause more suffering to the victims.

The majority of the victims underwent the same experience of sleep deprivation, exposure to freezing temperatures, deprivation from any means of warmth, including blankets. Nor did any victim stated that they had access to adequate nutrition or clean drinking water. Furthermore, all the victims were subjected to insults, expressions and conducts that touch their honor according to the prevailing social norms.

Detention has multi-faceted impacts on men, women and children including both physical and mental harm. The majority of the former detainees described suffering from chronic physical pain resulting from torture they sustained, let alone suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic attacks, constant fear, anxiety, isolation, compounded by recurring nightmares that exacerbate their trauma.

Legal Framework:

- Obligations of Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs) According to International Law:

In the context of IHL applicable on all areas included in this letter, this law regulates issues sufficiently related to the existing armed conflict. NSAGs exercise control on the civilian population by virtue of an armed conflict in which these groups have engaged in against the state. Accordingly, the IHL is applicable for the protection of those populations from exercising arbitrary authority by parties to the conflict in the absence or disruption of the protection supposed to be granted to them by national laws.[2] Therefore, NSAGs are obligated to apply a set of legal conventional and customary laws in dealing with civilians during armed conflicts, including at least “protection provided to the wounded and sick, protection of hospitals, principle of human treatment, prohibition of collective punishment, pillage, retaliation, and hostage-taking, prohibition of forced displacement and deportation, and the right to due process and judicial guarantees.”[3]

On the other hand, despite states have the primary responsibility for the respect, protection, and fulfilment of human rights under international law, there is a growing support for the approach saying that NSAGs in control of territories, and thus populations, assume obligations of IHRL to avoid a protection gap.[4] The UN endorsed this approach.[5] Furthermore, the Human Rights Council noted that “it is increasingly considered that under certain circumstances non-State actors can also be bound by international human rights law.”[6] Also, in their joint statement, human rights experts of the Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council concluded that “at a minimum, non-state armed actors exercising either government-like functions or de facto control over territory and population must respect and protect the human rights of individuals and groups.”[7]

The prohibition of torture, cruel, brutal, degrading treatment or punishment is a peremptory norm of international law (jus cogens). Prohibition, in this context, is not subjected to any justifications, limitations or pretexts related to the legal status of the concerned party. Prohibition is absolute in times of peace and war and is applicable to all actors without exception.

Within this context, Common Article 3 to the Geneva Convention applicable during non-international armed conflicts prohibits torture, cruel treatment and outrages upon personal dignity (inhuman treatment), in particular humiliating and degrading treatment; this prohibition is considered a reflection to Customary IHL.[8] It is important to note that the two terms of torture and inhuman treatment prohibited during armed conflicts do not require the participation or presence of a state official or of any other authority-wielding person in the torture process[9], as required by the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) . Accordingly, leaders and members of armed groups, in their capacity, assume legal liability for committing acts amount to torture or inhuman treatment without the need to argue the liability of the state in such acts. Commission of torture or inhuman treatment during non-international armed conflict entails individual criminal responsibility in case it fulfils elements of the crime of torture or inhuman treatment enshrined in the statutes of international criminal courts.[10] It is worth mentioning that the duty of human treatment is applicable in all circumstances and military necessity, or reciprocity may not be invoked as arguments against fulfilling this obligation by the opposing party to the conflict.[11]

Article 5 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) provides that “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”. Similarly, Article 2 of the CAT obliges state parties to refrain from acts of torture and to take effective legislative, judicial, and administrative measures to prevent acts of torture on their territories. Article 16 of the CAT obliges state parties to prohibit and prevent other acts of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment that does not amount to torture under their jurisdiction. Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) provides that “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Article 2 (2) of the CAT provides that “no exceptional circumstances, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.” Likewise, Article 4 (2) of the ICCPR clarifies that the obligation under Article 7 (prohibition of torture) cannot be derogated from in times of war or any kind of public emergency.

As a rule of the Customary IHL[12], arbitrary deprivation of liberty is prohibited. This is applied by analogy to its application to international armed conflict and also under IHRL. Accordingly, deprivation of liberty must be legitimate in the applicable law and comply with the essential procedures, most importantly: the arrested person must be informed of any charges, the person arrested or detained on a criminal charge shall be brought promptly before a judge, anyone who is deprived of liberty by arrest or detention has the right to take proceedings before a court to decide the lawfulness of the detention.[13] With respect to the legitimacy of deprivation of liberty, imperative reasons imposed during international armed conflict for an actor are limited to this deprivation only for utmost necessities if not for criminal causes are cited generally.[14] In addition, regardless of the causes of deprivation of liberty, all parties to the conflict are obligated to treat all persons under their control humanely and without discrimination in accordance with the first paragraph of the Common Article 3.

In the context of the IHRL, Article 9 of the UDHR prohibits acts of arbitrary arrest, detention, or exile. Article 9 of the ICCPR protects the right of individuals to liberty and security. Additionally, in paragraph 4, it provides that that anyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest or detention shall be entitled to take proceedings before a court, in order that that court may decide without delay on the lawfulness of his detention and order his release if the detention is not lawful.

In General Comment No. 35, the Human Rights Committee addressed the applicability of Article 9 of the ICCPR to situations of armed conflict, given that IHL regulates the detention of enemy fighters and civilians differently. The Human Rights Committee clarified that “article 9 [of the ICCPR] applies also in situations of armed conflict” and that IHL and IHRL are complementary spheres of law, not mutually exclusive.

Furthermore, while Article 9 is not included as a non-derogable clause under Article 4(2) of the ICCPR, there is a limit on state’s power to derogate. Any exception to Article 9 (which has not been done in the situation of Syria) must be “strictly required by the exigencies of the actual situation.” Lastly, “If, under the most exceptional circumstances, a present, direct, and imperative threat is invoked to justify the detention of persons considered to present such a threat, the burden of proof lies on states parties to show that the individual poses such a threat and that it cannot be addressed by alternative measures, and that burden increases with the length of the detention. States parties also need to prove that detention does not last longer than absolutely necessary, that the overall length of possible detention is limited and that they fully respect the guarantees provided for by article 9 in all cases.

By the growing consensus on the responsibility of NSAGs to respect and protect human rights in the areas they control, above-mentioned provisions are applicable to the SNA’s factions due to the fact that they continue to control the so-called “Peace Spring” and “Olive Branch” areas and perform functions similar to those of the Government.

[1] In the method of torture known as Blanco: the jailers suspend the detainees by the wrists to ropes dangling from the ceiling to force the detainee stand on the tip of their toes, so they are exposed to huge pressure or they remained hanged in the air so that the weight of their bodies press on their wrists and lead to the swelling of the wrists causing intense pain. Detainees may remain in such situation for hours or sometimes days in combination with severe beatings. While in the method of torture known as Farouja: the detainees’ hands and legs are tied together and are suspended on a wooden or a metal bar. Then, they are raised from above the ground to resemble the way of grilling a chicken in combination with beating on all over the detainees’ bodies.

[2] Official Records of the Diplomatic Conference on the Reaffirmation and Development of International Humanitarian Law applicable in Armed Conflicts, Vol. 8, CDDH/I/SR.22, Geneva, 1974–77, p. 201.

[3] Sivakumaran, The Law of Non-International Armed Conflict, (Oxford University Press, 2012), p 530.

[4]Committee Against Torture, 20th Sess., GRB. v Sweden, Communication No. 83/ 1997, UN. Doc. CAT/C/20/D/83/1997 (19 June 1998); Sheekh v Netherlands, App. No. 1948/04, HUDOC at 45 (11 January 2007); UN Secretary-General, Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, 243 (31 March 2011), p 188; Darragh Murray, Human Rights Obligations of Non-state Armed Groups (Hart Publishing, 2016).

[5] OHCHR, ‘International Legal Protection of Human Rights in Armed Conflict’, Geneva and New-York (2011), pp 23-27 (Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/HR_in_armed_conflict.pdf).

[6] Ibid. p. 24

[7] OHCHR, Joint Statement by independent United Nations human rights experts on human rights responsibilities of armed non-State actors, 25 February 2021 (Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2021/02/joint-statement-independent-united-nations-human-rights-experts-human-rights?LangID=E&NewsID=26797).

[8] Rule 90 of International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) regarding Customary International Humanitarian Law.

[9] ICTY, Kunarac Trial Judgment, 2001, para. 496, confirmed in Appeal Judgment, 2002, para. 148. See also Simić Trial Judgment, 2003, para. 82; Brđanin Trial Judgment, 2004, para. 488; Kvočka Appeal Judgment, 2005, para. 284; Limaj Trial Judgment, 2005, para. 240; Mrkšić Trial Judgment, 2007, para. 514; Haradinaj Retrial Judgment, 2012, para. 419; and Stanišić and ŽupljaninTrial Judgment, 2013, para. 49.

[10] Rome Statue, Article 8, C, (i) and (ii), statute of the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, Article 2 (b), statute of the international tribunal for Rwanda, Article 4.

[11] ICRC 2020 Commentary on Common Article 3, para 596.

[12] Rule 99 of the ICRC regarding Customary International Humanitarian Law.

[13] See for instance, Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 35, 2014.

[14] For instance, articles 42 and 78 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.