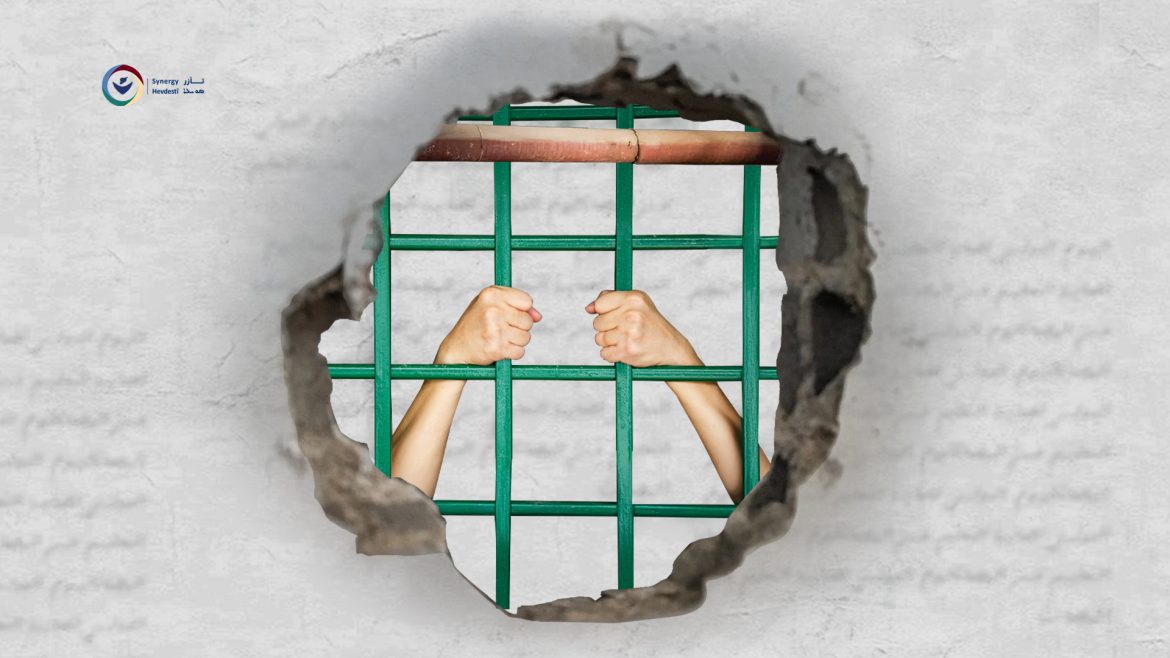

This report documents the continuous and systematic pattern of arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, and torture, practiced by factions of the SNA against the civilians in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tall Abyad with a direct support and funding from the Turkish government. In addition, the report examines the profound effects of these crimes on the victims, survivors, and their families, with a particular focus on the humanitarian and social dimensions of such crimes.

The report is based on 18 first-hand interviews, conducted with victims who were arbitrarily detained, tortured, and subjected to inhumane treatment in detention centers run by the SNA’s factions, affiliated with the Syrian Interim Government and the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces. The testimonies reveal systematic violations targeting civilians without any legal evidence or fair trails, as part of a policy aiming at consolidating the SNA’s control over the region and its residents.

The testimonies highlight the physical and psychological impacts resulting from violations, such as permanent injuries, physical deformities, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), chronic anxiety, depression, as well as other long-term emotional problems. They also reflect a broader societal impact of detention, manifested in social stigma, tarnished reputations, loss of employment opportunities, and economic hardships.

The report confirms that most cases of arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance were based on questionable accusations of collaborating with the Autonomous Administration or the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), or alleged involvement in terrorist activities. These violations highlight the absence of legal grounds and the use of arbitrary detention as a tool of political and social repression.

The testimonies clearly demonstrate that these accusations were used as tools for pressure and extortion, as the victims were often released after paying financial ransoms or spending months in custody without bringing any proven charges against them. Some victims reported that the primary aim of these practices was to force them to abandon their homes and properties, which were later confiscated and looted.

Furthermore, the report underscores the existing gap in justice and accountability mechanisms in these areas, allowing for perpetrators impunity, amid an environment rampant with chaos and conflict. On the other hand, the victims and their families face a shortage in the legal, psychological, and social support provided to them, heightening their suffering.

The report aims to highlight the bulk of humanitarian suffering ensued from arbitrary detention, torture, and enforced disappearance, while providing specific recommendations to strengthen legal protection mechanisms, provide the necessary support to victims and their families, and ensure accountability for those responsible for these violations to achieve justice and prevent their recurrence.

Arbitrary detention, torture, and enforced disappearance are among the gravest human rights violations, as their devastating effects extend beyond the period of detention to leave deep and long-lasting physical and psychological scars on victims, their families, and their communities. These practices are not isolated incidents, but rather a systematic tool used for political and social control, as clearly demonstrated in areas of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tall Abyad in Northern Syria.

The testimony of Hana[1], 26, a forcibly displaced woman from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê City, embodies a painful example of the suffering endured by the detainees. During her detention by SNA factions, Hana was subjected to various forms of torture, including beating with plastic cables (nicknamed al-Akhdar al-Brahimi), deprivation of food and health care, and psychological violence through constant threats of execution.

The detention conditions Hana endured were akin to a daily hell. She was held with other women in a cold, dark cell that lacked even the most basic necessities of life, resulting in severe health complications (bleeding and infections) that went untreated.

Hana’s suffering went beyond physical torture to include psychological humiliation. She was forced to witness the brutal torture of other detainees, with the constant threat that she would face the same fate unless she “confessed” to fabricated charges.

Although Hana was released after a month, her suffering did not end there. She faced cruel social stigma from her community. Instead of receiving support, she was subjected to bullying and attacks on her dignity. This drove her into a suffocating state of psychological and social isolation, making her a double victim- enduring the effects of physical torture, psychological humiliation, and social exclusion.

This experience highlights the devastating impacts of these violations, both on an individual and societal levels, and strengthens the urgent need to promote justice and accountability mechanisms to ensure perpetrators are held accountable and victims are compensated. Additionally, it emphasizes the necessity of providing inclusive programs to support the survivors, including psychological and social support, as well as community reintegration, to ensure that justice is an essential part of the recovery process.

On 9 October 2019, Türkiye commenced its military operation “Peace Spring,” initiating airstrikes and artillery bombardments on the region between Ras al-Ayn (Serê Kaniyê) and Tall Abyad, with impacts extending to areas like Kobani and al-Qamishli. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan publicly announced the operation, executed alongside Turkish-controlled NSAGs—primarily the Sultan Murad Division, the al-Hamza Division (aka Al-Hamzat), and Tajammu Ahrar al-Sharqiya (Ahrar al-Sharqiya), as well as the SNA Military Police.

During the initial days of the operation, more than 180,000 individuals, including thousands of women and children, were displaced in chaotic waves, as reported by the United Nations.[2] By the conclusion of the operation on 22 October 2019, Türkiye and its SNA proxies had seized a border strip approximately 120 km long and 30 km wide, stretching from Ras al-Ayn (Serê Kaniyê) to Tall Abyad. The displacement crisis left over 175,000 people uprooted, according to the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (COI).[3]

Notably, the COI has documented that civilians in Ras al-Ayn and Tall Abyad have experienced widespread violations of human rights and international humanitarian law (IHL), reflecting patterns of abuse previously recorded in the Afrin District. These violations—including abductions, detentions, extortion, torture, rape, and property seizures—are often committed with impunity.[4] The COI’s findings in this regard are constant in all its reports, indicating a steady and continuous systematic policy adopted and implemented by the reported NSAGs.

The report is based on a systematic and detailed analysis for the documented testimonies provided by 18 survivors (15 men survivors and 3 women) of arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance and torture, at the hands of SNA factions. The testimonies were collected between March and September 2024, using various methods to ensure the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the information. The methodology included both in-person and remote interviews with survivors or their families, adhering to strict privacy and security standards to protect the participants involved in the report.

The documented testimonies represent a diverse sample, including 14 victims of Kurdish ethnicity, three of Arab ethnicity, and one of Armenian ethnicity. The interviews followed a sensitive approach that respected the experiences of the survivors while adhering to principles of integrity and neutrality. Informed consent was obtained from all participants to use their testimonies in the report. To ensure privacy protection, pseudonyms were used for all cases at the request of the victims and witnesses.

A meticulous verification process, which included cross-checking information with other reliable sources, was applied to all of the testimonies and data. The findings were further strengthened by extensive expertise in documenting human rights violations and cooperation with international organizations, field researchers, activists, and other information sources, including reports from the United Nations and independent human rights organizations.

The testimonies were analyzed and organized to identify common patterns adopted in the conditions and methods of detentions, as well as their resulting impacts. The analysis focused on understanding the contexts in which these violations occurred and the political and social motivations behind them. The report showed that arbitrary detention was part of a systematic policy, aimed at imposing control, intimidating the indigenous people —particularly the Kurds—and depriving them of their fundamental rights.

The methodology devoted special attention to documenting the experiences of women survivors, given the nature of the violations they endured, which often involve gender-based violence. The testimonies included accounts of women subjected to psychological and physical humiliation, including threats of sexual violence, highlighting the urgent need to provide specialized psychological and social support for this group of survivors.

Despite the challenges faced during the documentation process, such as difficulties in accessing certain areas due to insecurity and lack of cooperation from the controlling parties, the report presents a comprehensive and cohesive depiction of the violations. This approach aims to raise awareness about human rights violations in the region and contribute to the development of mechanisms to protect victims and ensure accountability for these crimes.

None of the victims were promptly informed about the reasons for their detention. Most of them were arrested in their homes, while others were abducted in route or when engaging in their daily activities, such as managing their businesses. Additionally, Many witnesses were arrested while attempting to cross the border into Turkey on their way to migration. Despite this, they were later charged for alleged collaboration with the Autonomous Administration in North and East Syria (AANES), affiliation with the SDF, or involvement in acts of terrorism or sabotage.

Despite these charges, most detainees were never brought before a court or given the opportunity for legal recourse. Instead, they were often released only after paying ransoms or surrendering their properties. Additionally, those who did appear before a court were either forced to pay bribes or accused by judges of fabricating claims of torture and ill-treatment. All detainees were coerced into signing blank or pre-filled papers, which were later presented to judges as confessions.

Eight of the victims interviewed by Synergy lost large amounts of money, ranging from $1,000 to $10,000. The total amount of money seized from the victims—sometimes in dollars, others in Syrian Pounds, or in gold jewelry—exceeded $42,000.

These funds were collected through methods that reflect the state of chaos and lack of accountability in areas under the control of the SNA, including:

- Theft during detention: victims reported that their money and belongings were confiscated during their detention, including over $12,000 in cash, mobile phones, and other personal items.

- Raids and home theft: Money and gold jewelry were stolen from the victims’ homes during the raids, with some cases involving thousands of dollars in value.

- Direct financial ransoms: Families of the victims were forced to pay large amounts of money to ensure their release.

In a village located in the countryside of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê City, factions of the SNA launched a widespread arrest campaign detaining 25 Kurdish residents. The detainees were accused of carrying out explosions in the city without clear evidence being presented. Asim (41 years old), one of the victims, said:

“They stole around $800 from my house. It is a small amount compared to the gold and cash stolen from our neighbors, which was valued at around $6,000. The hardest part was being forced to leave the village entirely.”

The Kurdish families in the village were compelled to displace towards al-Hasakah City after selling their livestock at low prices. According to Sana, a 42-year-old, one of the displaced women:

“When we contacted residents in the area, we were shocked to learn that all our homes had been demolished as a collective punishment, and all the wooden pillars had been stolen.”

In the summer of 2020, Mahmoud, 35, attempted to return to his land in the western countryside of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê to harvest the wheat crop he had planted. However, members of Ahrar al-Sharqiya Faction intercepted him and accused him of collaborating with the Autonomous Administration and the SDF. Mahmoud was only released after paying a large financial ransom while his entire crop was stolen. Mahmoud estimated his losses, including the value of the stolen wheat crop to be over $2,500 according to the market prices at the time.

The testimonies documented by Synergy Association reveal the severity and conditions of detention inside the SNA’s prisons, that are often overwhelmed with poor ventilation and sanitation, in addition to lacking the most basic necessities for life. The victims unanimously agreed the food was scarce, limited to just one low-quality meal per day. Additionally, diseases such as scabies spread due to the deliberate neglect of healthcare.

Furthermore, the testimonies demonstrate that torture was a systematic part of the detention experience, with various methods used, including severe beating with plastic hoses, electrocution, sleep deprivation, and prolonged hanging. Other acts were aimed at humiliating the victims and breaking their will. These practices leave physical scars, such as fractures and deformities, as well as psychological effects that may last a lifetime.

Alongside the appalling conditions of detention and torture, many victims endured enforced disappearance, being denied contact with their families, and were held for prolonged periods without informing their families about their whereabouts or the charges filed against them.

Hana, 26-year-old, said: “I had no idea where I was being held, and they didn’t allow me to contact my family. They would threaten to execute me if I tried to ask about my fate.”

Abdulbaqi, is a 35-year-old man, whose painful account represents the nature of gross violations the civilians are facing in Northern Syria. He sustained a fractured foot while attempting to cross into Turkey seeking asylum. Instead of receiving medical care, he was beaten severely by Turkish Border Guards (gendarmerie) and then handed over to the Military Police forces of the SNA. Abdulbaqi’s health condition deteriorated due to deliberate neglect, ultimately leading to the amputation of his foot a month after the incident.

Abdulbaqi’s story started when he decided to cross into Turkey- illegally- from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, hoping to reach Europe in search of safety and asylum. Unfortunately, he suffered a severe injury when he broke his foot while attempting to jump over the four-meter-high border wall.

Instead of receiving the necessary treatment, Abdulbaqi was brutally beaten by the gendarmerie, who forced the group he was with to sleep on the ground in freezing temperatures. Later, they were handed over to the Civil Police of the SNA. Abdulbaqi’s condition worsened due to neglect, and after the intervention of mediators, the Civil Police agreed to transfer him to the public hospital in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. There, an X-ray was taken, and the doctors recommended immediate surgery for his foot in Turkey.

However, Abdulbaqi’s application to enter Turkey at the Syrian-Turkish border was rejected, and the gendarmerie accused him of being affiliated with the SDF. He was then handed over to the Military Police of the SNA, marking the beginning of a new ordeal. He was subjected to another round of interrogation, with a Turkish officer and an interpreter present. Abdulbaqi recalled:

“The Turkish officer kicked me for a long time and beat me with a quadruple cable whip. He repeatedly struck my broken foot with the intent to cause further harm. From his words, I understood he was insulting me and threatening to amputate my leg.”

Abdulbaqi was detained for 16 days, a period that drastically changed his life. Unable to endure the torture, he was forced to pay a ransom of $1,000 for his release. His condition worsened due to the lack of medical care during his detention, and after a month, his foot had to be amputated. Since then, Abdulbaqi has endured severe physical and psychological suffering due to his traumatic experience.

Salem, a 37-year-old man, narrates his harrowing experience during a month–and-a-half interrogation period in a solitary confinement, hardly enough for one person with no ventilation and sanitation at all. Salem endured daily torture, and was later transferred to the “Disciplinary Room” along with six others. He said:

“We used to drink water from the latrine hose. The room was extremely cramped. Yet, we were packed in it amidst filth and lack of ventilation. The conditions were catastrophic, with no adequate food and no respect for our humanity.”

Salem describes that period as a test of physical and mental endurance, where there was no hope other than just surviving.

On the other hand, Abdulla, 28 years old, faced similar conditions in the prison. Detainees were provided with only one meal a day, which was of very poor quality, and it was often accompanied by harsh insults from the guards. Although the detention conditions were generally deplorable, they were even worse during the interrogation periods, which sometimes lasted for months. One of the witnesses said:

“Sometimes I was denied food for days, and because of that, I would wait until they put rubbish bags inside the prison so I could eat the leftover food, which was often rotten.”

Torture sessions continued daily for several hours over 15 days, making him feel that death would be more merciful than this hell.

“Once, they tortured me by putting my head inside a bag and tying it around my neck until I couldn’t breathe and felt suffocated. During other sessions, they blindfolded me, and more than one person took turns torturing me.”

Abdulhamid’s story reflects the harsh methods used to torture detainees, aiming to break their will and force them to confess to fabricated charges. They threatened to assault his wife sexually, beat him over sensitive organs with the intent to affect his procreation abilities, and poured boiled water on his body as well.

Abdulhamid recalls one of the hardest moments when he was chained and dragged behind a pickup truck for 15 minutes.

“I was blindfolded and chained, and they dragged me behind a pickup truck for 15 minutes. After that, they electrocuted me several times, either on my head or by electrocuting the water on the ground. They also cut my body with blades and rubbed salt in the wounds to cause extreme pain.”

While the deplorable detention conditions added to the victims’ psychological and physical suffering, all of them testified that they endured torture in cruel, repeated, and systematic forms, reminiscent of the methods used in the notorious prisons of the Syrian regime.

In addition to individual stories, the testimonies show common torture methods used in detention centers run by the SNA forces, including physical suffering, sleep deprivation, and verbal abuse, all aimed at insulting and intimidating the detainees. The Kurdish detainees, in particular, were subjected to ethnic insults and other forms of racial abuse.

The torture methods described by the victims were varied but strikingly brutal, including beatings with sticks, electric cables, and rifle butts, as well as hanging from the ceiling, cigarette burns, and forcing detainees into painful positions such as “Shabah.”

Shabah position, also known as Blanco, involves suspending victims by their wrists with ropes hanging from the ceiling, forcing them to stand on the tips of their toes, which creates immense pressure. In some cases, detainees remain suspended in the air, with the weight of their bodies pressing on their wrists, causing swelling and intense pain. Detainees may be left in this position for hours or even days, often accompanied by severe beatings.

Another hanging position, called the “Farouja”, involves tying the detainees’ hands and legs together and suspending them from a wooden or a metal bar, lifting them off the ground. This method resembles grilling a chicken, combined with violent beatings across the detainees’ bodies. The torture often includes the use of a green hosepipe (a plastic hose typically used in plumbing and sanitary installations).

All the testimonies confirmed that torture was not merely a method to obtain information; rather, it was used as a tool to humiliate the victims and exert psychological control, leaving deep, lasting impacts that endure for a lifetime.

The testimonies of three women survivors who were detained by the SNA’s factions reveal that they were subjected to harsh psychological and physical abuses, including gender-based discrimination. These abuses were represented in the absence of any consideration to their needs as women. All of the interrogators and cell guards were men, exacerbating the cruel experience they went through.

Hana, 26, reported being detained with three others, who were all beaten with hoses and kicking, resulting in severe bleeding without receiving medical treatment. They were not provided any sanitary pads and were denied using the bathroom for prolonged times, resulting in urinary infections and skin allergies. After her release, Hana suffered from social stigma attacking her dignity and reputation; It was claimed that she was raped during detention. This situation prompted her to be isolated and introvert for a long time to evade the social stigma.

Sana, a 42-year-old survivor, talked about her suffering from electrocution, kicking, and food deprivation for two consecutive days, let alone insults of sexual nature during interrogation. Sana and other women with her were forced to listen to voices of men while being tortured, increasing the detention’s psychological impact. After her release, Sana and her family were forced to displace and sell all their properties. Her son is suffering from a severe psychological trauma causing in a stutter and chronic fear.

In addition to being tortured through kicking and beatings with green hoses, Safiya, 20, who was arrested when she was still 19, talked about the recurrent racist insults used by members of the Military Police during her detention. She was proscribed as a “pig” and referred to as the “tail of the criminal regime”. She also witnessed a violent assault on her father at the time of her arrest and was deprived of food for 24 hours. Safiya reported that her belongings, estimated to be worth $600, were stolen.

Many victims were able to identify the individuals involved in their detention and abuse, either through direct recognition or based on information provided by their captors. Some victims identified their captors based on their affiliations or the insignia displayed on vehicles, while others were informed of their captors’ factional affiliations by the captors themselves. However, some victims were blindfolded or otherwise prevented from identifying their captors.

Analysis of the testimonies and corroborating evidence indicates that these violations are part of a larger, coordinated system under the leadership of the SNA, encompassing its various factions, such as the Civil Police, Military Police, and Judiciary. The SNA factions and entities identified by the victims include Al-Hamzat, Sultan Murad Brigade, Military Police, Ahrar al-Sharqiyah, Ahrar al-Sham, and Jabhat Shamiyah.

United Nations bodies and international human rights organizations have documented similar patterns of violations against civilians in areas controlled by these SNA factions, particularly in Afrin and the “Peace Spring” areas. These include widespread arbitrary detention, forced displacement, extortion, torture, and sexual violence, particularly against Kurdish residents.

The evidence suggests that these violations may constitute systematic breaches of IHL and International Human Rights Law (IHRL). The pattern of abuse—ranging from arbitrary detention and looting to ethnic persecution—appears to be part of a broader strategy to displace the original residents, particularly the Kurds, and prevent their return. This strategy mirrors the practices observed during the “Olive Branch” operation in Afrin and has expanded in the “Peace Spring” areas.

These persistent and widespread abuses point to a systematic and well-coordinated campaign of violence and persecution, potentially sanctioned as official policy by the SNA factions. The goal appears to be the forcible displacement of Kurdish communities and the consolidation of control over the region through violence and intimidation. The practices that began in Afrin and spread to the “Peace Spring” areas continue to this day, with clear evidence of war crimes and human rights violations.

IHL regulates the behavior of all parties to an armed conflict, including NSAGs. NSAGs that control territories or populations due to their engagement in a non-international armed conflict are bound by IHL provisions that aim to protect civilians from arbitrary actions in the absence of State control.[5] They are required to respect a wide range of rights, including the protection of the wounded, the sick, and medical facilities, as well as the humane treatment of prisoners and detainees. They must refrain from practices like collective punishment, pillage, retaliation, and hostage-taking, and ensure that any forced displacement or deportation is in compliance with international law.[6]

The recognition of NSAGs’ obligations under international law, particularly regarding IHRL, is growing. While states remain the primary duty-bearers for human rights, NSAGs exercising control over territories are increasingly seen as responsible for safeguarding human rights within their domains.[7] The UN and the Human Rights Council have underscored that NSAGs controlling territories must respect human rights,[8] particularly when they function in ways similar to a government.[9] This duty includes ensuring the protection of both individual and collective rights of civilians under their authority.

Torture and inhuman treatment are prohibited under customary international law, with prohibition remaining absolute regardless of the circumstances, including during armed conflicts. This absolute prohibition applies to all actors, whether State or non-State, and is enshrined as a jus cogens norm—meaning that no derogation is allowed. Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, which applies to NIAC, mandates the humane treatment of all persons who are not actively participating in hostilities, and explicitly prohibits torture and inhuman treatment, including degrading or humiliating acts.[10]

NSAGs are bound by these rules even in the absence of State involvement. Acts of torture or inhuman treatment committed by NSAGs, such as during interrogations or detentions, are subject to individual criminal responsibility, regardless of whether they are sanctioned or carried out by the State.[11] International law does not permit NSAGs to justify such violations based on military necessity, nor does it allow the use of retaliation or other forms of reprisal as valid justifications for torture or ill-treatment.[12]

Key international instruments such as Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the Convention Against Torture (CAT), and Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) make it clear that the prohibition of torture and inhuman treatment is non-negotiable. CAT’s Article 2(2) reinforces that no exceptional circumstance can justify acts of torture, and similarly, ICCPR’s Article 7 explicitly prohibits torture under any conditions, including during times of war or public emergency.

International law prohibits arbitrary deprivation of liberty in both IAC and NIAC. Customary IHL,[13] in conjunction with IHRL, demands that any arrest or detention must be lawful and subject to judicial scrutiny. In particular, detained individuals must be informed of the charges against them and afforded the right to challenge the legality of their detention before a competent court.[14] NSAGs, as non-State actors exercising control over a territory, are similarly bound by these protections to ensure that arbitrary detention does not occur within their domains.

Article 9 of the UDHR and the ICCPR prohibit arbitrary arrest, detention, and exile, ensuring that any deprivation of liberty must be conducted in accordance with the law. In addition, ICCPR Article 9(4) grants individuals the right to take proceedings before a court to determine the lawfulness of their detention and secure their release if their detention is found to be unlawful.

The UN Human Rights Committee’s General Comment No. 35 affirms that the protections under Article 9 of the ICCPR apply even in situations of armed conflict, where IHL and IHRL overlap. In situations of armed conflict, States and armed groups must both respect the rights to liberty and security of those under their control. While States have the ability to derogate from some rights under Article 4 of the ICCPR during emergencies, any derogation from the protections against arbitrary detention must be narrowly tailored and strictly justified by necessity.

The principle of judicial review of detention remains paramount, and States (and, by extension, NSAGs) must ensure that detention is not prolonged beyond what is absolutely necessary. The burden of proof rests on the detaining authority to justify detention, and this burden becomes increasingly strict as detention continues. States and NSAGs must also ensure that detainees are treated humanely at all times, consistent with Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions.

The evolving understanding of NSAGs’ obligations to respect human rights further emphasizes the importance of adhering to these international protections in conflict zones. As these groups continue to govern territories, as seen in areas such as “Peace Spring” and “Olive Branch,” they must take on the responsibility of ensuring the protection of the human rights of civilians under their control. These obligations include safeguarding against torture, inhuman treatment, arbitrary detention, and other human rights violations, regardless of the state’s capacity to protect or enforce these rights.

Given the seriousness of the violations perpetuated and the absence of legal protection for thousands of civilians who are at risk, whether they are current or potential victims on the long-term, the SNA’s factions in control of Northern Syria must be aware that they do not enjoy impunity and that they are obliged to respect human rights for the residents under their control.

Following the fall of the Syrian regime on December 8, 2024, these recommendations constitute a road map for the process of promoting human rights in areas of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tall Abyad, with ensuring accountability for the perpetrators and achieving justice for the victims. These efforts must be part of an inclusive international response to ensure the end of violations and providing a sustainable protection for the affected residents.

Recommendation to the UN and Governments of the Member States:

- Conduct transparent and comprehensive investigations into the gross violations of human rights in the SNA-controlled area, and widely publish the results of these investigations to ensure accountability.

- Prosecute the people responsible for the violations in accordance with the universal jurisdictions, especially in the countries where their laws allow prosecution of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

- Collect and preserve evidence to be submitted to the national and international courts with the aim of holding the perpetrators and all those involved accountable.

- Ensure investigations in the crimes pointed against women, especially the crimes that include gender-based violence, and establish centers designated for survivors of arbitrary detention and sexual violence that provide specialized psychological and legal services.

- Impose international sanctions on the individuals and entities responsible for the violations in Syria, including the crimes committed in the aforementioned areas.

- Force the Turkish government- since it exercises effective control on the SNA- to comply with its obligations under the International Humanitarian Law (IHL), protect civilians lives, and hold accountable its affiliated factions.

- Pressure the SNA’s factions and all the de facto powers to provide essential judicial guarantees for the detainees, including their right to know the charges pointed against them and receive a fair trial.

- Release, promptly and unconditionally, all the arbitrary detained people, and abolish all the sentences based on confessions extracted under torture.

Recommendations for Local and International Human Rights Organizations:

- Provide psychosocial support programs for survivors of arbitrary detention and torture, as well as to families of enforced disappearance, taking into account the women and children’s needs.

- Provide legal and community support for the victims to ensure integration in their society and their effective participation in transitional justice processes.

- Promote legal documentation skills and report the violations systematically and professionally.

- Release periodic reports highlighting the ongoing violations, and organize international advocacy campaigns to urge the international community to take practical steps.

- Promoting solidarity with the survivors through initiatives calling for their protection and support.

Recommendations to Promote Transitional Justice:

- Support national and international efforts to collect and store the evidence to ensure they are used in future trials.

- Establish a national record to document cases of arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, and torture to ensure recognition of the victim and pursue their cases.

- Develop a comprehensive mechanism for transitional justice that includes compensating the victims, rehabilitation programs, and clear accountability procedures.

- Establish local truth and reconciliation committees working on uncovering the truth concerning the crimes and ensure they do not recur.

- Ensure voluntary, safe, and dignified return of the survivors and displaced to their houses, restitution of rights, and they are not subject to oppression or revenge.

- Secure fair compensations for the violations-affected people, including enforced disappearance and property looting.

You can read the full Report (14 pages) through the link.

[1] Hana is a pseudonym for a survivor who gave a testimony to Synergy Association for Victims. Her real identity and information that can refer to her are withheld for her security and safety.

[2] UNHCR, More than 10,000 Syrians crossed the Iraqi border since the onset of the Turkish campaign on Northeast Syria, the United Nations, 25 October 2019 (Available at: https://news.un.org/ar/story/2019/10/1042501).

[3] UN General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, A/HRC/34/57, 28 January 2020, para 45.

[4] See, for example: Amnesty International, Syria: Damning evidence of war crimes and other violations by Turkish forces and their allies, 18 October 2019 (Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2019/10/syria-damning-evidence-of-war-crimes-and-other-violations-by-turkish-forces-and-their-allies/).

[5] Official Records of the Diplomatic Conference on the Reaffirmation and Development of International Humanitarian Law applicable in Armed Conflicts, Vol. 8, CDDH/I/SR.22, Geneva, 1974–77, p. 201.

[6] Sivakumaran, The Law of Non-International Armed Conflict, (Oxford University Press, 2012), p 530.

[7]Committee Against Torture, 20th Sess., GRB. v Sweden, Communication No. 83/ 1997, UN. Doc. CAT/C/20/D/83/1997 (19 June 1998); Sheekh v Netherlands, App. No. 1948/04, HUDOC at 45 (11 January 2007); UN Secretary-General, Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, 243 (31 March 2011), p 188; Darragh Murray, Human Rights Obligations of Non-state Armed Groups (Hart Publishing, 2016).

[8] OHCHR, ‘International Legal Protection of Human Rights in Armed Conflict’, Geneva and New-York (2011), pp 23-27 (Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/HR_in_armed_conflict.pdf).

[9] OHCHR, Joint Statement by independent United Nations human rights experts on human rights responsibilities of armed non-State actors, 25 February 2021 (Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2021/02/joint-statement-independent-united-nations-human-rights-experts-human-rights?LangID=E&NewsID=26797).

[10] Rule 90 of International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) study on Customary International Humanitarian Law.

[11] ICTY, Kunarac Trial Judgment, 2001, para. 496, confirmed in Appeal Judgment, 2002, para. 148. See also Simić Trial Judgment, 2003, para. 82; Brđanin Trial Judgment, 2004, para. 488; Kvočka Appeal Judgment, 2005, para. 284; Limaj Trial Judgment, 2005, para. 240; Mrkšić Trial Judgment, 2007, para. 514; Haradinaj Retrial Judgment, 2012, para. 419; and Stanišić and ŽupljaninTrial Judgment, 2013, para. 49.

[12] ICRC 2020 Commentary on Common Article 3, para 596.

[13] Rule 99 of the ICRC Study on Customary International Humanitarian Law.

[14] See for instance, Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 35, 2014.